Time management: the leadership meta-problem.

When you sit down for coffee with a manager, you can probably guess the biggest challenge on their mind: time management. Sure, time management isn’t always everyone’s biggest challenge, but once the crises of the day recede, it comes to the fore.

Time management is the enduring meta-problem of leadership. For most other aspects of leadership you can look to more experienced managers and be reassured that things will get better, but in this dimension it appears that the most tenured folks are the ones most underwater. Yes, their degree of difficulty is certainly higher, but it’s intimidating to consider there’s little evidence that most folks ever get a solid grasp of their time.

Does that make this a lost cause? Nah.

I’m still pretty busy on a day-to-day basis, but I’ve gotten much, much better at getting things done, not by getting faster, but by getting more consequent. The most impactful changes I’ve made to how I manage time are:

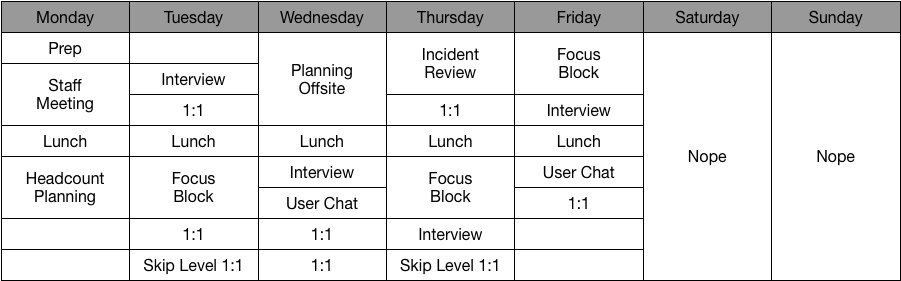

- Quarterly time retrospective. Every quarter I spend a few hours categorizing my calendar from the past three months to figure out how I’ve invested my time. This is useful for me to reflect on the major projects I’ve done, and also to get a sense of my general allocation of time. I then use this analysis to shuffle my goal time allocation for the next quarter.

Most folks are skeptical of whether this is time well-spent, but I’ve found it particularly helpful, and it’s the cornerstone of my efforts to be mindful with my time. - Prioritize long-term success over short-term quality. As your scope increases, the important work that you’re responsible for may simply not be possible to finish. Worse, often the work you believe is most important, perhaps high quality one-on-ones, is competing with work that’s essential to long-term success, like hiring for a critical role. Ultimately, you have to prioritize long-term success, even if it’s personally unrewarding to do so in the short-term. It’s not that I like this approach, it’s that nothing else works.

- Finish small, leveraged things. If you’re doing leveraged work, then each thing you finish should create more bandwidth to do more future work. It’s also very rewarding to finish things. Together these factors allow large volumes of quick things to build into crescendoing momentum.

- Stop doing things. When you’re quite underwater, a surprisingly underutilized technique is to stop doing things. If you drop things in an unstructured way, this goes very poorly, but done with structure this works every since time. Identify some critical work that you’ll not do, recategorize that newly unstaffed work as organizational risk, and then align with your team and management chain that you won’t be doing it. This last bit is essential: it’s fine to drop things, but it’s quite bad to silently drop them.

- Size backwards, not forwards. A good example of this is scheduling skip-levels. When you start managing a multi-tier team, say twenty folks, you can specify a frequency for skip-levels and reason forwards to figure out how many hours of skip-levels you’ll do in a given week. Say you have 16 indirect reports, and you want to see them once a month for thirty minutes, so you end up doing two hours per week.

This stops working as your team grows, because there is simply no reasonable frequency that won’t end up consuming an unsustainable number of hours. Instead, specify the number of hours you’re able to dedicate to the activity, perhaps two per week, and perform as many skip-levels as possible within that amount of time. This keeps you in control of your time allocation and scales as your team grows. - Delegate working “in the system.” Wherever you’re working “in the system,” design a path to someone else taking that work on. It might be that this plan will take a year to come together, and that’s fine, but what’s not alright is if it’s going to take a year and you haven’t even started.

- Trust the system you build. Once you’ve built the system, at some point you have to learn to trust it. The most important case of this is handing off handling exceptions. Many managers hold onto the authority to handle exceptions for too long, and at that point you lose much of the system’s leverage. Handling exceptions can easily consume all of your energy, and either delegating them or designing them out of the system is essential to scaling your time.

- Decouple participation from productivity. As you get more senior, you’ll be invited to more meetings, and many of those meetings will come with significant status. Attending those meetings can make you feel powerful, but you have to keep perspective about whether you’re accomplishing much by attending. Sometimes being able to convey important context to your team is super valuable, and in those cases you should keep attending, but don’t fall into the trap of assuming attendance is valuable.

- Hire to slightly ahead of growth. The best gift of time management that you can give yourself is hiring capable folks, and hiring them before you get overwhelmed. By having a clear organizational design, you can hire folks into roles before their absence becomes crippling.

- Calendar blocking. Creating blocks of time on your calendar is the perennial trick of time management: add three or four two-hour blocks scattered across your week to support more focused work. It’s not especially effective, but it does work to some extent and is quick to set up, which has made me a devoted user.

- Getting administrative support. Once you’ve exhausted all the above tools and approaches, the final thing to consider is getting administrative support. I was quite skeptical of whether admin support is necessary, and until your organization and commitments reach a certain level of complexity they aren’t, but at some point having someone else handling the dozens of little interrupts is a remarkable improvement.

As you start using more of these approaches, you won’t immediately find yourself less busy, but will gradually start to finish more work. Over a longer time horizon, thought, you can get less busy by prioritizing finishing things with the goal of reducing load. If you’re creative, consequent and don’t fall into the trap of believing being busy is being productive, you’ll find a way to get the workload under control.