Talent distributions.

When I was applying to college some years ago, one of my teachers asked if I thought I would regret not applying to more prestigious schools, making the observation that it’s not whether the professors would be good–the professors are good everywhere–but rather about the quality of the student body. Would I learn from my peers?

I hadn’t thought of that conversation in a decade, but it floated up through the layers of memory when someone recently asked why I originally joined Stripe.

Much like a school’s student body, talent distributions at a company reflect their values. Learning about a company’s distribution is an effective proxy for learning about their intended and actual cultural values, and neatly sidesteps the expected questions that folks are sometimes too careful to answer directly (e.g. is fairness important at your company?).

In my opinion, a company’s policies and their approach to policy enforcement are the truest representation of their values: they’re where folks make the hard tradeoffs between conflicting values. For example, everyone values both impact and partnership, and it’s only in the depths of policy enforcement that those values come into conflict and their relative merits are fully weighed.

Let’s look at how talent distributions are impacted by:

- allocation of innovation work,

- performance management and compensation,

- and end with a refrain on working the policy, not the exception.

Off we go!

What is talent?

The definition of talent I’m using here is “productive and happy.”

I prefer this definition because I believe a company’s talent distribution is generally a reflection of how many folks they allow to perform at a high level, not a reflection of those folks’ inherent ability.

Other definitions sometimes implicitly reflect a fixed mindset that talent is something intangible that folks either do or do not have, which doesn’t map well with my personal experience. Folks change. Sometimes for worse, but very often for the better. (Both are most often caused by external factors in their life).

Where does innovation happen?

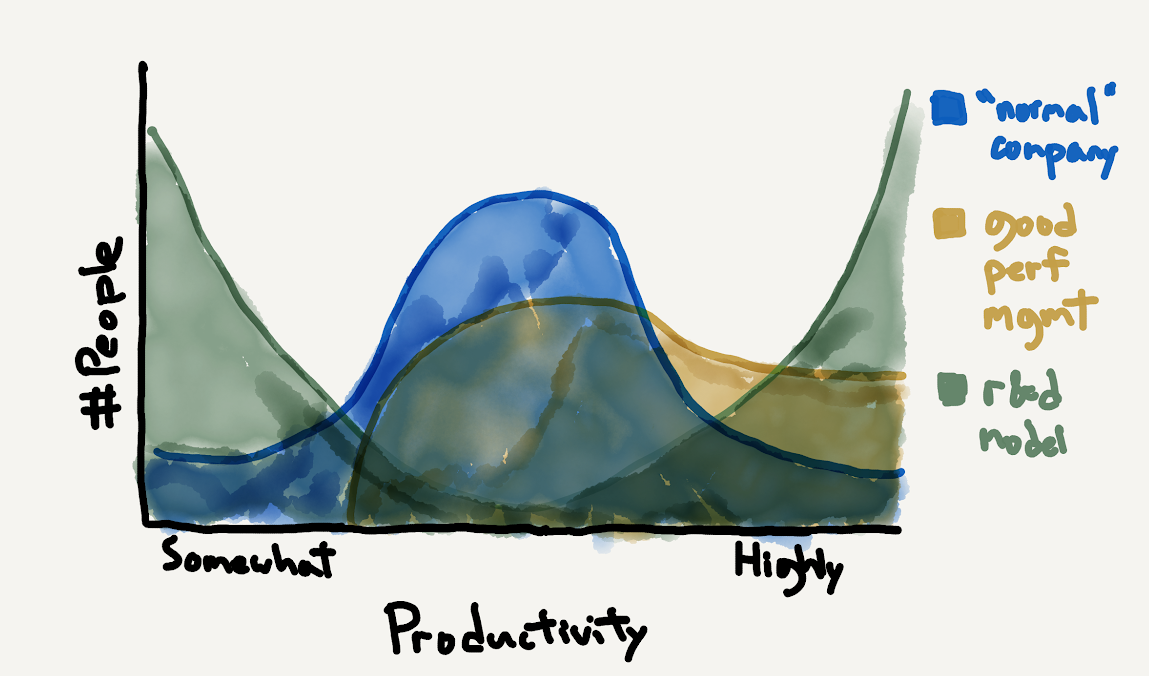

My experience is that companies with uniformly productive folks have an egalitarian bent, and those with multimodal productivity distributions prefer specialization or hierarchy.

The most obvious examples of this is looking at where innovation happens. The two most common models I’ve seen are:

- Full ownership model - the same teams are responsible for innovation and maintainance.

- Research & development model - maintenance teams are responsible for work that supports immediate business value, innovation teams build things with potential future business value that they’ll hand off to maintenance teams.

The full ownership model leads to a tighter talent distribution, where most folks across the company are experiencing similar productivity. That doesn’t necessarily mean that everyone is more productive; in cases where teams are seriously underwater due to deadlines or technical debt, this model can mean that everyone’s productivity is tightly grouped at the low end of the scale.

However, and this is my most important point, the full ownership model is also the only way to have uniformly high performance across a company. You have to earn it through good management, but it’s possible, and it’s been done before.

Conversely, the research & development model signals that you either don’t believe it’s possible or important for everyone to be productive, and that you’d rather select a subset of folks to be highly productive and another subset to be less. This leads to two tightly grouped clusters of productivity, at the top and the bottom of the scale.

Generalizing what factors do and don’t facilitate uniformly high performance, companies with high variance in productivity tend to:

- promote internal competition - this creates the conditions for zero sum outcomes, with winners and losers.

- tolerate local optimization - many companies ask folks to do the right thing for the broader company, but lack mechanisms to identify and correct folks who are misaligned. More often due to lack of information to be aware they’re misaligned than any sort of bad intent. A special case of this is over-competing for resources such that other more constrained teams can’t obtain resources.

Conversely, companies that have tightly clustered productivity, albeit not necessarily at top end, tend to:

- minimize hierarchy and specialization - such that most folks work on most kinds of work, and are able to shift to higher priorities according to global needs.

- centrally regulate consumption of shared resources - in an organization with reduced hierarchy, the role of central authorities is to correct imbalances and inefficiencies within the loose self-organization. This is especially important as the organization gets large enough that most folks lack context to globally optimize.

Summarizing this section: the sole pathway to uniformly high productivity is to adopt an egalitarian approach to innovation and couple it with excellent management.

Performance and compensation

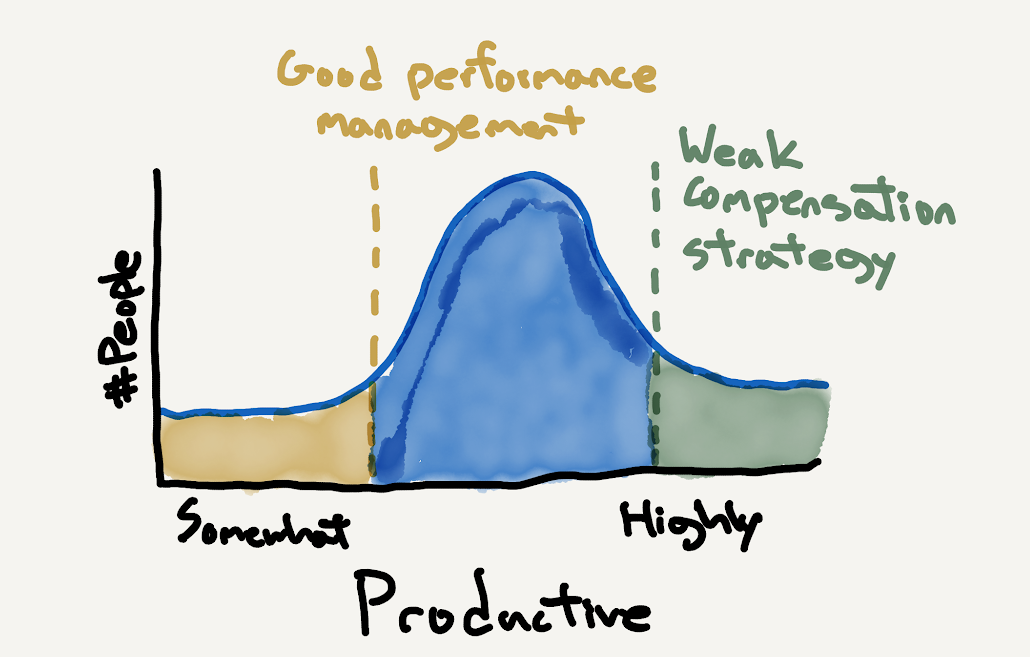

Once you’ve accounted for the impact of organizational design, the most literal levers for increasing the talent distribution of your company are performance management and compensation strategy.

Every company says they value high performance teams and manage out folks with weaker performance, but most companies and managers are uncomfortable doing this. There are lots of reasons why performance management is uncomfortable. Because you have a growth mindset, you believe that folks can improve, so you want to give them time to improve. Because you value a sense of community, you don’t want to make folks feel at risk by letting their peers go.

Having some deliberate policy around performance makes this easier, creating a gentle push for managers to set a clear plan and timeframe with folks who are struggling to figure it out together. Without this mild pressure, folks tend to defer conflict for too long.

Compensation strategy, sometimes called compensation philosophy, is the other piece here. Folks want to work at companies whose mission they belief in, with peers they appreciate, but I find most folks will sacrifice both if they believe they’re missing out on compensation to do so. Even when acknowledging they should value their happiness over compensation, folks simply can’t value happiness over money.

Conversely, you’ll also find folks who are paid so well that they remain in jobs that they’ve come to detest because they don’t believe they can find an alternative with similar compensation. My experience is that this is more about compensation liquidity than it is about total compensation, which is why I’m very positive about recent trends towards longer exercise windows and such.

Policy over exceptions

Designing good policy is 10% of translating your values into an organization that reflects thoes values, and the remaining 90% depends on how you handle exceptions. Policy enforcement is forever the blur tool in your organizational toolkit: applied thoughtfully it can more beautiful than the original crisp lines, but enough inconsistency and it’ll ruin the entire picture.

Where have you been most productive?

What made it work?

Was your productivity at the expense of others?