Introduction to systems thinking.

Many effective leaders I’ve worked with have the uncanny knack for working on leveraged problems. In some problem domains, the product management skillset is extraordinarily effective for identifying useful problems, but systems thinking is the most universally useful toolkit I’ve found.

If you really want a solid grasp on systems thinking fundamentals, you should read Thinking in Systems: A Primer by Donella Meadows, but I’ll do my best to describe some of the basics and work through a recent scenario where I found the systems thinking approach to be exceptionally useful.

Stocks and flows

The fundamental observation of systems thinking is that the links between events are often more subtle than they appear. We want to describe events causally–our managers are too busy because we’re trying to ship our current project–but few events occur in a vacuum.

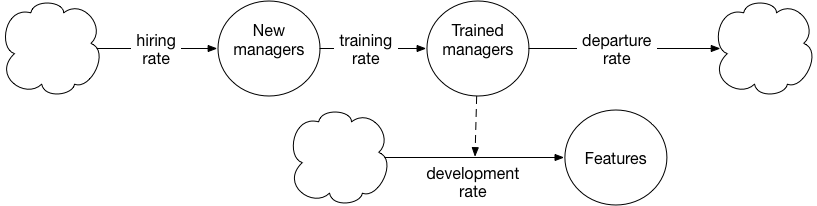

Big changes appear to happen in a moment, but if you look closely underneath the big change, there is usually a slow accumulation of small changes. In this example, perhaps the managers are busy because no one hired and trained the managers required to support this year’s project deadlines. These accumulations are called stocks, and are the memory of changes over time. A stock might be the number of trained managers at your company.

Changes to stocks are called flows. These can be either inflows or outflows. Training a new manager is an inflow, and a trained manager who departs the company is an outflow. Diagrams in this article represent flows with solid dark lines.

The other relationship, represented in this article by a dashed line, is an information link. These indicate that the value of a stock is a factor in the size of a flow. Indicated in this diagram by a dashed line. The link here shows that the time available for developing features depends on the number of trained managers.

Often stocks outside of a diagrams scope will be represented as a cloud, indicating that there is something complex happened there that we’re not currently exploring. It’s best practice to label every flow, and to keep in mind that every flow is a rate, whereas every stock is a quantity.

Developer velocity

When I started thinking of a useful example of where systems thinking is useful, one came to mind immediately. Since reading Forgren’s Accelerate earlier this year, I’ve spent a lot of time pondering their definition of velocity.

They focus on four measures of developer velocity:

- Delivery lead time is time from code being written to it being used in production.

- Deployment frequency is how often you deploy code.

- Change fail rate is how frequently changes fail.

- Time to restore service is time spent recovering from defects.

The book uses surveys from tens of thousands of organizations to assess their overall producitivty and show how it correlates to their performance on those four dimensions.

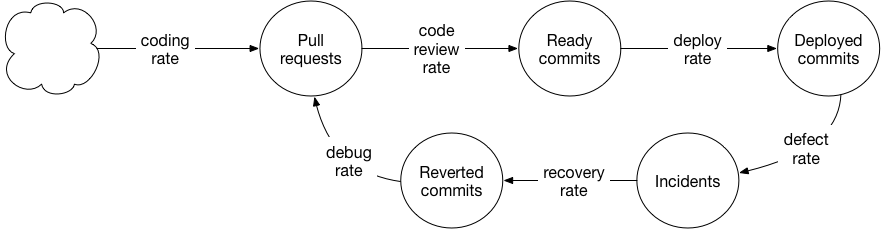

These kind of intuitively make sense as measures of productivity, but let’s see if we can model these measures into a system we can use to reason about developer productivity:

- pull requests are converted into ready commits based on our code review rate,

- ready commits convert into deployed commits at deploy rate,

- deployed commits convert into incidents at defect rate,

- incidents are remediated into reverted commits at recovery rate,

- reverted commits are debugged into new pull requests at debug rate.

Linking these pieces together, we see a feedback loop, where the system’s downstream behavior impacts its upstream behavior. With a sufficiently high defect rate or slow recovery rate, you could easily see a world where each deploy leaves you even further behind.

If your model is a good one, opportunities for improvement should be immediately obvious, which I believe is true in this case. However, to truly identify where to invest, you need to identify the true values of these stocks and flows! For example, if you don’t have a backlog of ready commits, then speeding up your deploy rate may not be valuable. Likewise, if your defect rate is very low, than reducing your recovery time will have little impact on the system.

Creating an arena for quickly testing hypothesis about how things work, without having to do the underlying work beforehand, is the aspect of system thinking that I appreciate most.

Model away

Once you start thinking about systems, you’ll find it’s hard to stop. Pretty much any difficult problem is worth trying to represent as a system, and even without numbers plugged in I find them powerful thinking aids.

If you do want the full experience, there are relatively few tools out there to support you. Stella is the gold standard, but the price is quite steep, costing more than a new laptop for non-academic licenses. The best cheap alternative I’ve found is InsightMaker, which has some UI quirks but has a donation based payment model.