Stripe's model of product-led, developer-centric growth.

Recently, I got an email from someone asking about Stripe’s approach to product-led, developer-centric growth. If you really want a unique insight into Stripe, you’re undoubtedly better off reading Stripe’s 2021 update, but here are my general notes on Stripe as a microcosm of product-led, developer-centric growth.

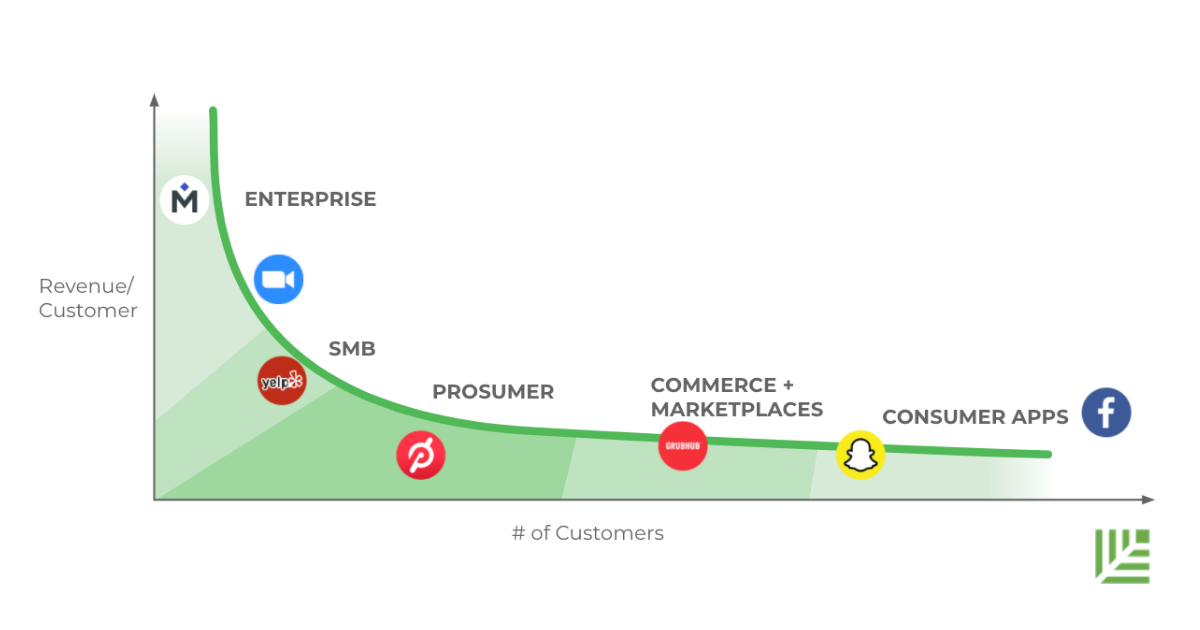

from Sequoia's The Market Curve

A good place to start this journey is with the market curve, with this one specifically from Sequoia, which segments companies by the customer cohort they serve. The Stripe of 2022 spans from SMB through enterprise, but early Stripe was highly focused on the startup segment of SMB.

Startups are a particularly interesting segment of SMB because they have:

- a lightweight vendor selection process, similar to many SMBs

- they’re often operating in a single country and currency (in the US, anyway)

- don’t have the historical baggage of longer lived SMBs

- unlike most SMBs, they have developers for a technical integration

- a small percentage are likely to become very large within 3-4 years

Stripe’s initial product and their approach to product-led growth was exceptionally tailored to startups as well:

- every company needs payments from the very beginning, but they don’t need a comprehensive, broad payments solution until much later

- self-service allows customers to start intregrating immediately

- Stripe’s approach to account approval (approval is finalized in time for the first payout rather than the first collected payment) further reduces friction relative to industry peers at the time

- Stripe’s pricing model (taking a percentage of transactions) doesn’t require an upfront payment or payment guarantee, which means many startups are able to entirely skip their internal approval flow, which would pull the finance team, and a number of other internal buyers, into the process

The final essential piece of the Stripe’s strategy is being developer-centric:

- early startups generally have a higher percentage of developers than any other sort of business

- developers buying a developer product in a startup generally don’t require any cross-functional resources to integrate the product (as long as it’s self-service and doesn’t require a large cash commitment). This isn’t true for almost any other buyer and almost any other company size

- developers, particularly those working in startups, are reachable across a small number of communities (VCs, incubators, Twitter, Hackernews, etc)

- developers would generally rather engage with self-service than a sales person (so self-service isn’t just a better margin solution, for a developer-centric product focused on startups it’s a genuinely better solution overall)

The combination of these three factors, in addition to Stripe’s selection of a central problem (payments), and willingness to take business risk (e.g. risk of fraud) in their pursuit of developer-centric, product-led growth (e.g. self-service to production, not just to development), was a major contributor to Stripe’s early success. That said, it was the execution of this strategy, rather than solely the idea of this strategy, that set Stripe apart from other companies executing a similar strategy at the time.

Stripe was surprisingly far along before they had a meaningful marketing or sales team (“meaningful” in quantity, the extraordinarily small early teams were very capable), but inevitably they did build out those functions. The reason they built them out was simply: they wanted to expand into the enterprise channel, and the product-driven approach doesn’t work particularly well there.

Product-driven growth is a weak fit in enterprise because:

- enterprise buyers expect significant human involvement in the sales process

- enterprise buyers hang out in very different places than developers, which means marketing needs to be approached differently

- enterprise businesses expect a structured contracting process, including meaningful legal review

- enterprise businesses expect to a detailed negotiation around pricing

- developers are rarely the most important buyer in enterprise vendor selection, and are often not an improtant buyer at all

- much more than early startups, enterprises care about comprehensiveness of features

Thus Stripe built out the traditional mechanisms of enterprise sales and marketing. What’s surprising, and one of the most compelling elements of Stripe’s approach, is their continued emphasis on startups despite the enterprise sales buildout:

Our first customers were friends who were starting companies, and we still spend a lot of time with startups. We try to better understand what they’re up to, what they need, and what could help more get started. We want to support startups from the first lines of code through IPO and beyond+

That Stripe has managed to pursue both enterprise and startups simultaneously is one of their major accomplishments. They did it primarily by:

- Strategically, having a clear strategic rationale for investing in the startup segment even after the enterprise segment started to gain traction. Their financial model understands how startups grow over time into enterprise businesses, which makes it possible to rationally balance investment into both startup and enterprise, which many companies struggle with.

- Tactically, isolating individual teams from the tension between enterprise and startup buyers. Certainly there are some exceptions, but generally the team working on Atlas is prioritized exclusively against the needs of early-stage startups, and the team working on Payments is prioritized exclusively by the needs of enterprise customers.

Throwing a few more disjoint ideas into the mix:

- It’s easier to expand from product-led growth to enterprise than vice-versa. The former requires a high level of automation and easy onboarding, whereas the later is easy to hack with human-driven processes

- Starting with a very clear buyer is extremely valuable. You can hyperfocus your marketing and sales effort in tone and approach far more effectively. In particular, with a very narrow buyer, you can do things like e.g. become a key part of the incubators where those buyers show up at the time they’d need to buy your product. This is much more effectively than writing blog posts, even if you write great blog posts. Similarly, there are very difficult things you can do that represent differentiated access to these buyers, e.g. Stripe Atlas is a difficult product to offer, but allows Stripe access to startups even if they aren’t connected to any incubator or venture capitalist

- At certain moments in growth, you will have to expand your channels of prospects. The key thing is to do that deliberately (make sure you’re actually winning with your current set of prospects) and to avoid sacrificing your existing channels (dedicate resources to existing channels as well). It would have been easy for Stripe to fall into a reverse Innovator’s Dilemma when they started selling into enterprise, and the fact that they did not make that mistake is one of their key strengths

- The information pipeline from sales to product is a key part of winning at enterprise. For example, enterprise buyers will care a lot about compliance and things like SOC2, which startup buyers may not think about as all. Without an effective mechanism for sales-to-production information propagation, you’ll have a rough go of it

- Effective support across multiple tiers, playing with responsiveness, correctness and depth is particularly essential for enterprise onboarding

- Developers are a unique buyer because they don’t require any other function to integrate the products they buy. IT is potentially the other buyer in this category, but unfortunately they’re generally viewed as a cost center by most companies, so they’re a less leveraged buyer

- Stripe also has a partner program and a small number of strategic partnerships that help it with distribution. Partnerships are an important piece of the broader puzzle, particularly in the ways that strategic partnerships provide distribution

- A constructive, collaborative partnership between sales, product and legal is another easy-to-miss but essential aspect of success. Many companies don’t notice the absence until they dig into their pipeline analytics and notice significiant friction in the contracting stage (which is, it’s important to emphasize, not “just a problem with legal” but instead the manifestation of a partnership gap across, at least, these three functions)

I’m sure there’s much, much more that should be mentioned here, but since my goal is a relatively concise writeup to answer an email, rather than writing the canonical reference for all-time, I’ll leave it at this, but if there are particularly important pillars that I missed out, drop me a note!