Distributing your Slack application.

We’ve been working on the reflect Slack application for a while,

and it’s almost done. We just have to make

it possible for other folks to install it.

The golden standard of distribution is Slack’s App Directory,

which makes it easy for folks to find and install your app.

We won’t quite get our toy app into the App Directory, but we will make it possible for other folks to install it into their workspaces, at which point you could submit it to the directory if you wanted.

We’ve already done quite a bit, we just need to integrate with Slack’s OAuth implementation to get workspace-scoped OAuth tokens and update our API requests to use those tokens instead of the hard-coded tokens we’ve used thus far. Hopefully this is easy…

post starts at commit 4584 and ends at commit 0fcc

Slack app in Python series

- Creating a Slack App in Python on GCP

- Adding App Home to Slack app in Python

- Make Slack app respond to reacji

- Using Cloud Firestore to power a Slack app

- Distributing your Slack application

Distributing Slack applications

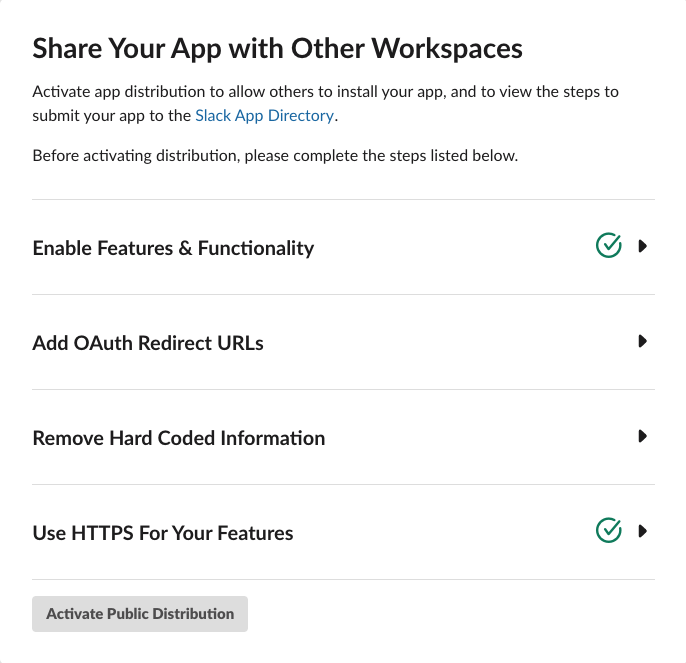

To distribute a Slack app, there is a helpful checklist in the App admin. Google Functions are run over HTTPS, so we already have that covered. You might consider LetsEncrypt if you’re using a different host and need free SSL.

We’ve also already enabled quite a bit of functionality over the course of the series, starting with the Slash Commands, App Home, some Events, and so on. So we’re good there too.

The remaining two are Add OAuth Redirect URLs, which we’ll get into next,

and Remove Hard Coded Information. The later is just a checkbox asserting

that you’ve done it, but… we haven’t done that yet since we have a bunch

of tokens in our env.yaml, so we’ll come back to that after finishing the

OAuth flows.

Steps to integrate OAuth

To integrate with Slack’s OAuth, we’re going to need to:

- Implement an OAuth redirect URI that accepts the

codetoken from the OAuth flow and exchanges the token for long-lived OAuth tokens. - Register that new redirect URI with Slack.

- Store those long-lived tokens in Firestore so that we can retrieve the appropriate tokens based on the request’s team.

- Use the team-appropriate tokens for API requests, no longer

using the tokens we’ve stored in

env.py. - Construct our authorization URL, which is where we’ll redirect users in order for them to authenticate.

- Verify that our OAuth integration flow fully works.

- Update existing flows to use stored tokens.

There are a lot of details to keep straight here so it can get a bit confusing, but fortunately the actual code we need to write is on the simpler side. Onwards!

OAuth redirect URI

We’re going to create a new Cloud Function that will handle

the redirect.

We’ll start by updating reflect/storage.py to support

storing the retrieved tokens.

DB = firestore.Client()

def credentials(team_id):

return DB.collection('creds').document(team_id)

def set_credentials(team_id, data):

creds = credentials(team_id)

creds.set(data)I love that we can just shove the JSON response into Firestore without deconstructing it. Admittedly, we might want to be a bit more careful in validating the contents in a production application to guard against future changes to the data format.

Then we’ll update reflect/api.py to support calling

oauth.access

which requires a slightly different format than the other two

API integrations we’ve done so far.

def oauth_access(code):

url = "https://slack.com/api/oauth.access"

client_id = os.environ['SLACK_CLIENT_ID'].encode('utf-8')

client_secret = os.environ['SLACK_CLIENT_SECRET'].encode('utf-8')

data = {

'code': code,

}

auth = (client_id, client_secret)

resp = requests.post(url, data=data, auth=auth)

return resp.json()Then we’ll update reflect/main.py to add the new

function oauth_redirect which we’ll turn into

a Cloud Function in a bit.

from api import oauth_access

from storage import set_credentials

def oauth_redirect(request):

code = request.args.get('code')

resp = oauth_access(code)

team_id = resp['team_id']

set_credentials(team_id, resp)For this to work, we’ll need to add SLACK_CLIENT_ID

and SLACK_CLIENT_SECRET to reflect/env.yaml.

Those values are in the Basic Information tab in

your App admin.

SLACK_CLIENT_ID: "your-client-id"

SLACK_CLIENT_SECRET: your-client-secret

SLACK_SIGN_SECRET: your-secret

SLACK_BOT_TOKEN: your-bot-token

SLACK_OAUTH_TOKEN: your-oauth-token

GOOGLE_APPLICATION_CREDENTIALS: ./gcp_creds.json

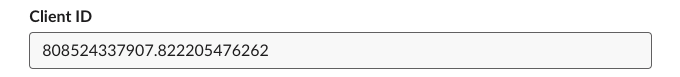

Note that you’ll need to wrap your Client ID in quotes because otherwise Cloud Functions will attempt to treat it as a float, which will fail.

Then deploy our new Cloud Function so that we can get its URI.

cd reflect

gcloud functions deploy oauth_redirect \

--env-vars-file env.yaml \

--runtime python37 --trigger-http

Next up, registering the URL.

Register redirect URL

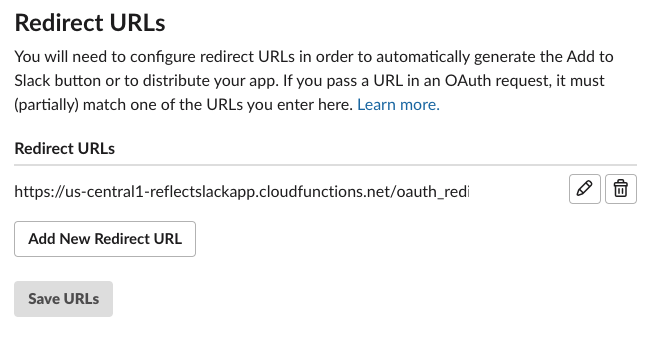

The URL we got when creating the oauth_redirect endpoint

will look something along the lines of this.

https://your-url.cloudfunctions.net/oauth_redirect

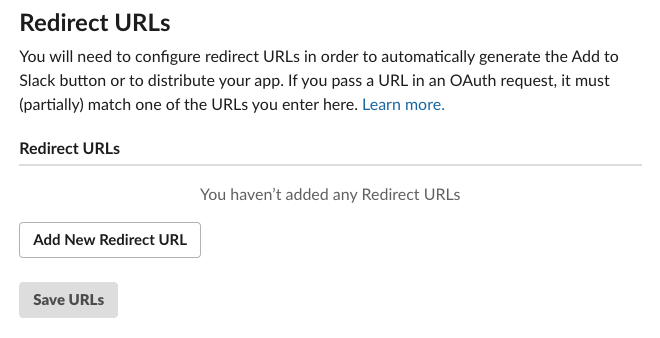

Now we need to go to the App admin, navigate to OAuth & Permissions on the left nav, and go to Redirect URLs.

Click on Add Redirect URL, paste in the URL, and click Save URLs.

Excellent, we’re one step further.

Create OAuth authorization URL

To authorize folks, we want to redirect them to

https://slack.com/oauth/authorize

We need to include two GET parameters: (1) client_id to identify our application,

and (2) scope of requested permissions required by our app.

There are additional parameters you can send, documented in Using OAuth 2.0,

but which we can ignore for now.

There is also a streamliend approached called Direct Install URL that is available for applications in the App Directory, which unfortunately is not us. Further, you can’t get into the App Directory until you’ve integrated this OAuth flow, so there’s no skipping these steps.

Let’s start by constructing this URL by hand.

First we’ll grab out client_id by going into our App admin,

selecting Basic Information on the left navigation, and scrolling

down to App Credentials.

In this case, our Client ID is 808524337907.822205476262.

Then in App admin we should go to OAuth & Permissions and note the four scopes we’re using:

bot

commands

channels:history

reactions:read

Taking all of these, we can generate the authorization URL.

https://slack.com/oauth/authorize

?client_id=808524337907.822205476262

&scope=bot,commands,channels:history,reactions:read

Also note that you can get this generated for you by heading over to Manage Distribution in the App Admin now that you’ve added a Redirect URL (it doesn’t show up until you’ve added one). It’s pretty nifty, autogenerating an embeddable button for you, as well as the authorization link for your app with the correct scopes.

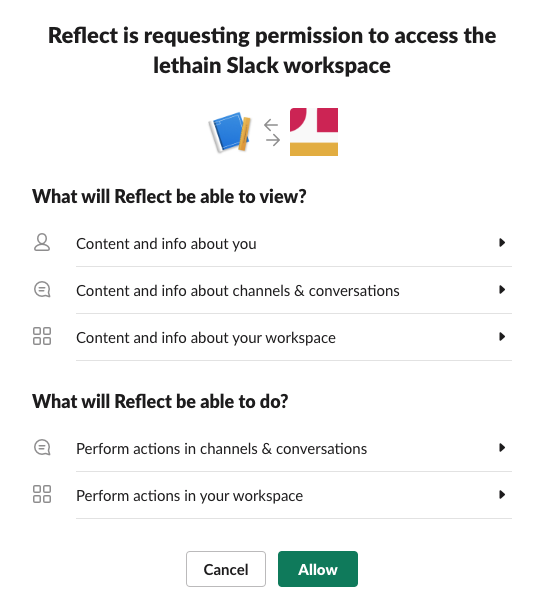

Verifying the flow

Now that we have our authorization URL, paste it into your browser and it’s time to see if it actually works.

Click Allow and it’ll redirect to our handler above, and then you’ll see

a mostly white webpage with the text OK. Long term, you’ll likely want

to redirect the user somewhere more helpful through a 301 response to

our oauth_redirect Cloud Function.

Slack recommends using their deep linking.

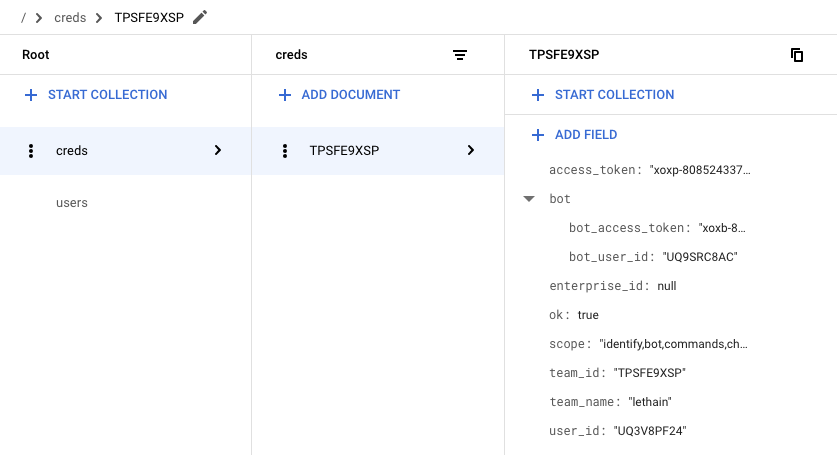

If we head over to Firestore, we can verify that we captured the data we want.

We did, which is quite exciting: we’re almost done with our OAuth integration. We just need to update our calls into the Slack API to use these retrieve tokens instead of those we’ve previously hardcoded.

Using the tokens

We’re capturing OAuth and bot tokens from the OAuth authorization flow,

so the first thing we should do is delete our hardcoded tokens in our

reflect/env.yaml file.

delete -> SLACK_BOT_TOKEN: your-bot-token <- delete

delete -> SLACK_OAUTH_TOKEN: your-oauth-token <- delete

SLACK_CLIENT_ID: your-client-id

SLACK_CLIENT_SECRET: your-client-secret

SLACK_SIGN_SECRET: your-secret

GOOGLE_APPLICATION_CREDENTIALS: ./gcp_creds.json

Then we’ll add a function to reflect/storage.py to

retrieve our credentials.

def get_credentials(team_id):

creds = credentials(team_id).get().to_dict()

return {

'oauth': creds['access_token'],

'bot': creds['bot']['bot_access_token'],

}Then we’ll need to modify reflect/api.py to

grab credentials using get_credentials.

# retrieving bot token previously

os.environ['SLACK_BOT_TOKEN'].encode('utf-8')

# updated

get_credentials(team_id)['bot']

# retrieving oauth token previously

os.environ['SLACK_OAUTH_TOKEN'].encode('utf-8')

# updated

get_credentials(team_id)['oauth']There is one minor caveat, which is that retrieving these

tokens requires threading the team_id into each of the function

calls that query the Slack API. This requires refactoring

reflect/events.py a bit. Fortunately team_id

is included in all the events that we’re subscribed to,

making it easy to thread through.

Afterwards, deploy the latest version of dispatch,

and it should work. Verify by testing our /reflect,

/recall, visting the App Home, and using a reacji.

Enabling distribution

Assuming everything above worked, then head back to Manage Distribution, scroll down to Remove Hard Coded Information, and confirm that you have.

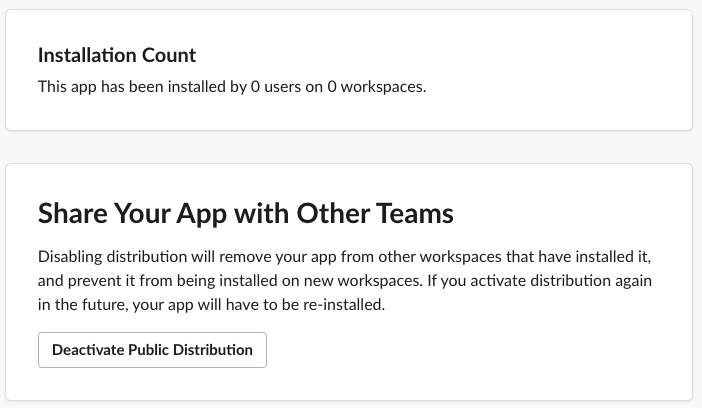

At which point the Activate Public Distribution button will enable, which you should click.

After enabling distribution for your app, you’re able to see your installation count, disable distribution, as well as enter a workflow to submit your application to the Slack App Directory, most importantly though: if you share the authorization URL with someone, they can install your app.

Another way to say this is: we’re done!

Some reflections

Over the course of these five entries, I’ve gotten to spend a good amount of time with both Slack’s API and Google’s function-as-a-service offering, Cloud Functions. Both were moderately delightful.

Slack

I started this series with the hypothesis that building an application on Slack’s platform would be easier than building a comparable web application. At the end, I think that hypothesis held true for this project. Starting up new projects requires a tremendous amount of scaffolding, and Slack has done a phenomenal job of providing quick-to-implement interfaces that absolve you from writing scaffolding, even if you eschew their Python SDK and write raw integrations, which I did to learn more about the underlying APIs.

You could argue that SDKs are the real interface for modern APIs, because the vast majority of integrations go through language specific SDKs rather than generating raw API calls, but I’ll leave that argument for a different post.

Slash Commands are very comfortable for me with a text-based past, and I’m curious if others are equally comfortable with them or if there is something of an split between folks who grew up using IRC and folks who did not. I do think there’s a clear argument for Reacji as modernized Slash Commands with better discoverability.

Overall I think reacji-as-user-interface is a particularly fun and interesting

area to explore in Slack applications, and I imagine Slack has some pretty powerful

data on usage patterns. One nit is that I wish I could filter incoming reaction events

based on the specific reactions, e.g. only get events for the :ididit: reaction

instead of having to filter out all of them. The volume of irrelevant reactions is

so much higher than the volume of reactions any given app would care about, and

skipping out on that network traffic seems ideal.

The two areas where the Slack API and platform feel most like a work-in-progress are (1) constrained expressivity and (2) API inconsistency.

When I started formatting the list of completed tasks, I ran into an interesting

problem: neither Block Kit nor mrkdwn support lists. Instead you can create a sort

of raw Markdown-ish list by shoving each item into its own paragraph, but it’s not quite

right, and it’s even further from a Dropbox Paper-esque

dynamic, shared checklist. Often genius comes from constraints,

and Slack’s constraints in expression are driving innovation like reacji,

but it remains true that a web or native application has a stagger amount of flexibility

to express its ideas, and today Slack apps do not.

It’s the natural state of long-lived platforms to end up with some inconsistency in their APIs, and Slack shows a fair amount of their evolution in their API. It’s also the case that the consistency of their API design is constrained by the inconsistencies in web standards: Slack can’t make the OAuth flows consistent with their Events API, because the OAuth flows are an aging standard they must adhere to. This essential inconsistency required by implementing web-standards while also offering modern API behavior is a real challenge, and SDKs are really the only path around it, which Slack is certainly doing.

Overall, I think the completeness of the Slack platform and ease of building on it is quite exciting, and I can only imagine where it’ll be in a few more years.

GCP

Developing on Cloud Function was the lowest overhead project scaffolding

I’ve experienced, allowing me to get started almost instantly.

Running Python servers is particularly annoying–I’ve spent enough time configuring

uWSGI, thanks–and I got to skip all of that and just write the application-specific code.

Adding requirements.txt dependencies worked as expected, copying files in directory for extra data

worked as expected, being able to pass in environment variables worked well, etc.

Cloud Firestore was also surprisingly easy to set up and use. The query patterns are very constrained, but as a document store that takes no administrative overhead to setup, it just worked for this usecase. I have so many toy projects that I never operationalize because dealing with storage is a pain or expensive, and I think many of those projects might be going into Firestore in the future.

The biggest gap in Cloud Functions as they stand today is that it’s surprisingly hard to put them behind a load balancer without writing your own software, which is straightforward on AWS. This might not be necessary for autoscaling purposes as the function scheduler is an orchestration system in its own right, but it is necessary in terms of getting behind a single SSL connection, being able to multiplex requests across multiple resources on one HTTP/2 connection, presenting a professional veneur of running behind your own domain, and to have a clean interface behind which you could shift your implementation over time.

Altogether, I really enjoyed this project and particularly it reminded me how joyful it is to write small-scale software in Python. I hope these notes are useful to someone, and drop me a note with your thoughts.