Sizing engineering teams.

When I transitioned from supporting a team to supporting an organization, I started to encounter a new category of problems I had never thought about. How many teams should we have? Should we create a new team for this initiative or ask an existing team to take it on? What is the boundary between these two teams?

These questions were the gateway to the obscure art of organizational design. As I’ve gotten more exposure, I’ve come to believe the fundamental challenge of organizational design is sizing teams. You’ll find yourself sizing teams during reorganizations, to accommodate growth from hiring, and when considering how to support new projects. It’ll be an unusual month that you won’t consider some aspect of team design.

While I’m skeptical that there exists a unified law of team sizing, I have iterated onto a useful framework that solves the majority of cases I encounter. That framework has in turn led to a standard playbook. Both are short, opinionated and hopefully useful!

The guiding principles I use for sizing teams are:

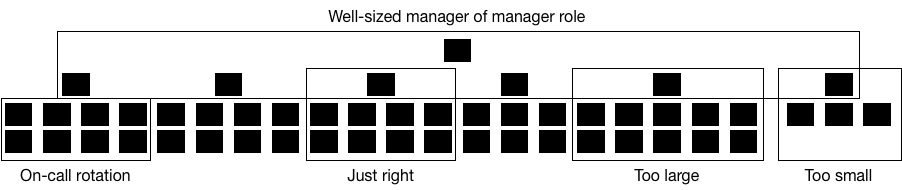

- Managers should support 6-8 engineers. This gives them enough time for active coaching, coordinating and furthering their team’s mission by writing strategies, leading change, and so on.

- Tech Lead Managers (TLMs). Managers supporting less than four engineers tend to function as TLMs, taking on a share of design and implementation work. For some folks this role can uniquely leverage their strengths, but it’s a role with limited career opportunities. To progress as a manager, they’ll want more time to focus developing their management skills. Alternatively to progress towards staff engineering roles, they’ll find it difficult to spend enough time in the technical details.

- Coaches. Managers supporting more than eight or nine engineers typically act as a coach and a safety nets for problems. They are too busy to actively invest into their team or their team’s area of responsibility. It’s reasonable to ask folks to support larger teams during the transition to a more stable configuration, but it is a bad status quo.

- Managers should support 4-6 managers. This gives them enough time to coach, align with stakeholders and to do a reasonable amount of investment into their organization. On the other hand, it will also keep them busy enough that they won’t be tempted to create work for their team.

- Ramping up. Managers supporting fewer than four other managers should be in a period of active learning on either the problem domain or in transitioning from supporting engineers to supporting managers. In the steady state, this can lead to folks feeling underutilized, or be tempted to meddle in daily operation.

- Coaches. Similarly to supporting large teams of engineers, supporting a large team of managers leaves you functioning purely as a problem-solving coach.

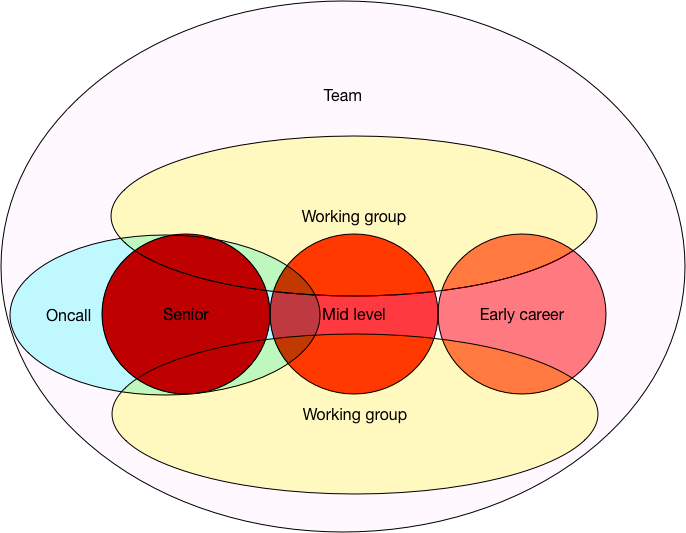

- Oncall rotations want 8 engineers. For production oncall responsibilities, I’ve found that two-tier 24/7 support requires eight folks. As teams holding their own pagers has become increasingly mainstream, this has become an important sizing constraint, and I try to ensure every engineering team’s steady state is eight folks.

- Shared rotations. It is sometimes necessary to pool multiple teams together to reach the eight folks necessary for a 24/7 oncall rotation. This is an effective intermediate step towards teams owning their own oncall rotations, but it is not a good long-term solution. Most folks find being oncall for components they’re unfamiliar with to be disproportionately stressful.

- Small teams (<4) are not teams. I’ve sponsored quite a few 1-2 person teams, and each team I’ve regretted it. To repeat: I have regretted it every single time. An important property of teams is that they abstract the complexities of the individuals that compose them. Teams with fewer than four folks are a sufficiently leaky abstraction that they function indistinguishably from individuals. To reason about a small team’s delivery, you’ll have to know about each oncall shift, vacation, and interruption. They are also fragile, with one departure easily moving them from innovation back into toiling to maintain technical debt.

- Keep innovation and maintenance together. A frequent practice is to spin up a new team to team to innovate while existing teams are bogged down in maintenance. I’ve historically done this myself, but I’ve moved towards innovating within existing teams. This requires very deliberate decision making and some bravery, but in exchange you’ll get higher morale, a culture of learning, and avoid creating a two-tiered class system of innovators and maintainers.

Fitting together those guiding principles, the playbook that I’ve developed is surprisingly simple and effective:

- Teams should be six to eight during steady state.

- To create a new team, grow an existing team to eight to ten, and then bud into two teams of four or five.

- Never create empty teams.

- Never leave managers supporting more than eight folks.

Like all guidelines, this is a structure to aid thinking through sizing problems, not a straightjacket to slam shut every exception. The context of any situation deserves careful examination, but increasingly I’ve found the long-term cost of exceptions to outweigh what I once considered their strengths.