Roles over rocket ships, and why hypergrowth is a weak predictor of personal growth.

There’s a pervasive trope that folks who’ve worked an extended period in a large company will struggle to adapt to working in a smaller company. Work at a company too long, the theory goes, and you’re too specialized to hire elsewhere.

This belief is reinforced by both age bias and the reality that few companies continue to win the rounds of reinvention necessary to maintain excellence over time. The pool of once phenomenal companies is quite large: Yahoo, Oracle and VMWare, to name a few.

If long tenure holds a stigma, what of short tenure? Yup, that’s stigmatized too. Although, certainly less stigmized then it used to be. A fairly consistent belief across companies is that multiple stints below one year are a bad sign, but generally as long as you’ve worked a few years somewhere, then having a career that is otherwise entirely composed of one year stints raises few red flags.

While I’m certain these beliefs are, at best, deeply flawed, they’ve accidentally become a rule of thumb in my own career: stay everywhere at least two years, and look for a place I could spend four years to serve as the counterweight to my series of two year stints. I’ve followed this rule very literally, staying at least two years (well, we can all count here, exactly two years) at each company I’ve worked at, and starting each job with the hope that this one would be the place I’d make it to four.

To the surprise of no one, it turns out that’s been a pretty terrible way to think about career planning, and lately I’ve been trying to find a more useful framework.

Working at a company isn’t a single continuous experience, rather it’s a mix of stable eras and periods of rapid change that bridge between eras. Thriving requires both finding a way to succeed in each new era, and successfully navigating the transitional periods. You trigger some transitions, like switching companies. Others happen on their own schedule: a treasured coworker leaves, your manager moves on, or the company runs out of funding.

Discard the discussion of tenure, let’s talk about eras and transitions.

Your new career narrative

Start by building out a map of your past year. Each time there was a change that meaningfully changed how you work, mark that down as a transition. These could be your direct manager changing, your team’s mission being redefined, a major reorganization, whatever: what counts is if how you work changed. What skills did you rely on to navigate the transition? What skills did the transition give you an opportunity to develop?

Next, thing about the eras that followed those transition. How did the values and expectations change? Did operational toil become considered critical work? Did work around inclusion and diversity become first shift work that gets mentioned in performance reviews? What skills did you depend on the most, and which of your existing skills fell out of use?

What you just wrote down is your new career narrative, and it’s much richer than just another year at your company.

Opportunities for growth

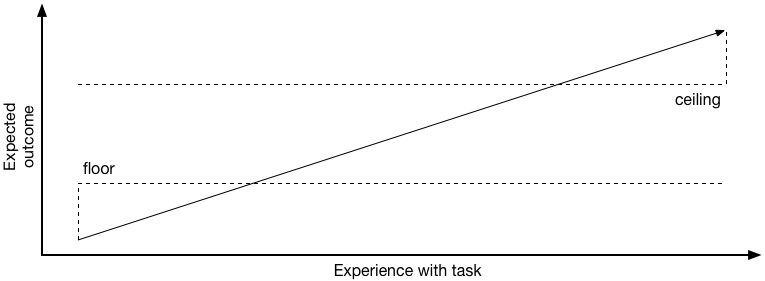

The good news is that both the stable eras and the transitions are great opportunities for growing yourself. Transitions are opportunities to raise the floor by building competency in new skills, and in stable periods you can raise the ceiling by developing mastery in the skills that new era values. As the cycle repeats, your elevated floor will allow you to weather most transitions, and you’ll thrive in most eras by leveraging your expanding masteries.

It’s suggested that mature companies have more stable periods and startups a greater propensity for change, but it’s been my experience that what matters most is the particular team you join. I’ve seen extremely static startups, and very dynamic teams within larger organizations. I particularly want to challenge the the old refrain:

If you’re offered a seat on a rocket ship, don’t ask what seat! Just get on.

- Sheryl Sandberg

Even hypergrowth companies tend to have teams that are largely sheltered from change by either their management or because they’re too far away from the company’s primary constraints to get attention.

By tracking your eras and transitions, you can avoid lingering in any era beyond the point where you’re developing new masteries. This will allow you to continue your personal growth even if you’re working in what some would describe as a boring, mature company. The same advice applies if you’re within a quickly growing company or startup: don’t treat growth as a forgone conclusion, growth only comes from change, and that is something you can influence.

Thanks to Jay, Jorge and Wynn for reviewing versions of this post.