Reading a Profit & Loss statement.

Some years ago, I was explaining to my manager that I was feeling a bit bored, and they told me to learn how to read a Profit & Loss (P&L) statement. At the time, that sounded suspiciously like, “Stop wasting my time,” but operating in an executive role has shifted my perspective a bit: this is actually a surprisingly useful thing to learn. The P&L statement is a map of a company’s operation and is an effective tool for pointing you towards the most pressing areas to dig in.

While there is a lot of depth to reading a P&L, this will walk you from zero to one, and will hopefully take a bit less than thirty minutes. I’ll start by reviewing the components of a P&L statement, describe the steps I use to review a P&L, show an example of applying those steps, and end with instructions for finding public companies P&L statements to practice on.

What’s in a P&L statement

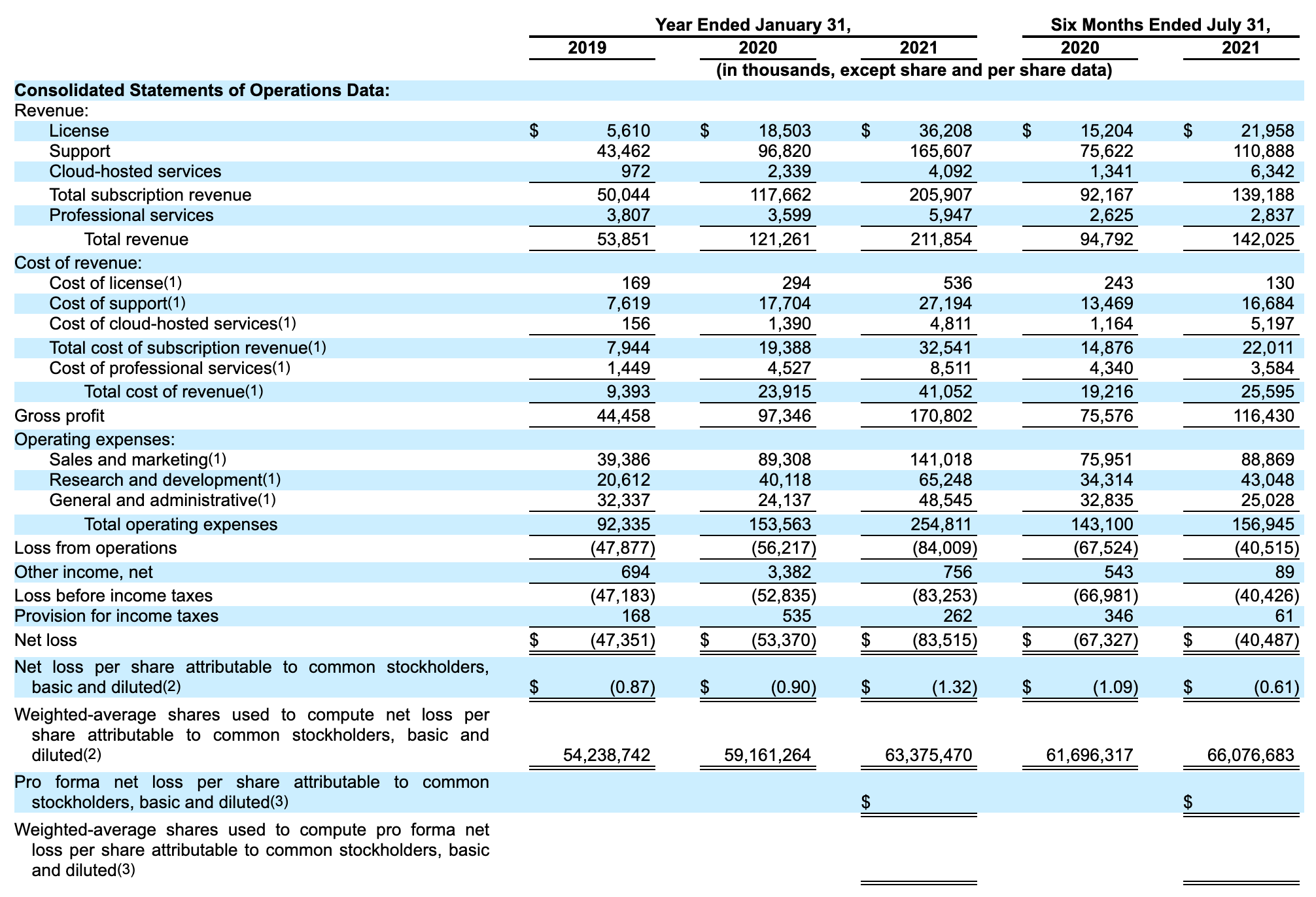

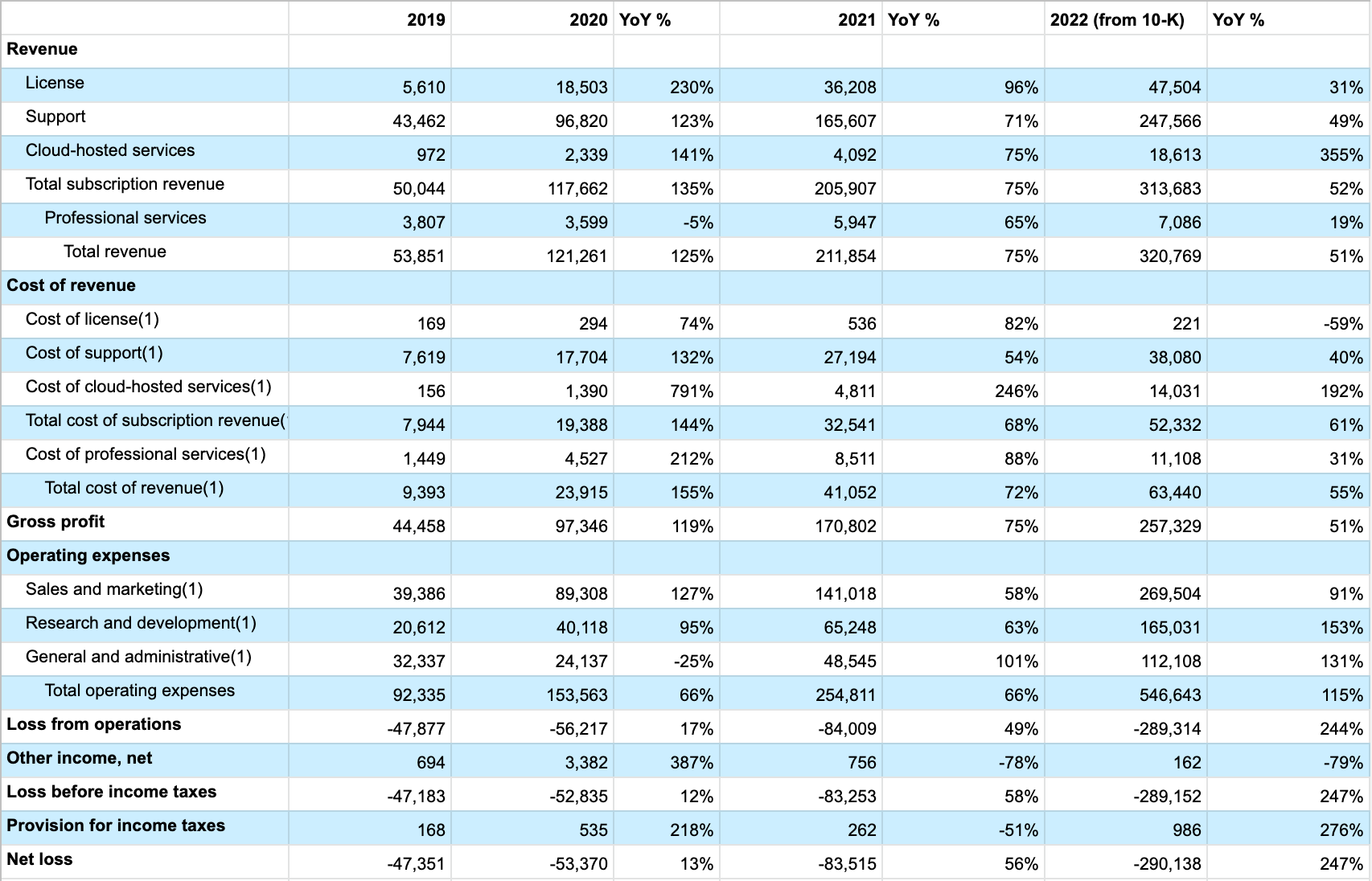

In order to review a P&L statement, we need a P&L statement to read, and I’ve selected Summary Consolidated Financial Data from page 18 of HashiCorp’s S-1 filing. It’ll be helpful to have that at hand to refer to throughout.

There’s a lot there! First let’s look at the top headers. The first three columns are showing revenue for 2019 through 2021. All numbers here are “in thousands”, meaning that $18,503 is actually $18,503,000 and so on. The last two columns are looking at six month windows. We’re trying to get a sense of the business overall, to let’s focus on the annual numbers.

When you’re looking at internal data, it’s particularly important to understand where a table shifts from historical data to forecast data. It’s very common when talking with an early-stage startup that they’ll include their somewhat optimistic current year forecast as part of their financial data. Public companies, on the other hand, essentially never share forecasts. All S-1s, 10-Ks and similar documents are historical data. There are cases when reported data initially appears to be a forecast, for example some companies end their Financial Year in January, which is the case here for Gitlab: their 2021 Financial Year only runs through January 31st, 2021, so their 2021 results are not a forecast even though this report was issued on November 4th, 2021. (Consequently, the majority of Gitlab’s 2021 performance would only become available in their 2022 Finance Year report.)

Next, lets take a look at the columns. The sections are:

- Revenue across a few different business lines (license, support, etc). This is how much money is booked by each business line. For example, “Support” brought in $43m of revenue in 2019

- Cost of revenue for each business line. This is the cost of producing the revenue. For example, “Cloud-hosted services” spent $156k in 2019 (to generate their $972k in revenue)

- Gross profit is “total revenue” minus “total cost of revenue”. This is how much profit the company would make if it had no operating expenses. For example, $170m in gross profit in 2021

- Operating expenses is how much money was spent operating the business. For example, $153m in 2020

- Loss from operations is “gross profit” plus “other income, net” minus “operating expenses”. For example, $83m in 2021

- Net loss is “gross profit” minus (“loss from operation” plus “provision for income taxes”). For example, $47m in 2019

There are a few more rows, but everything else you can ignore from the perspective of understanding the business.

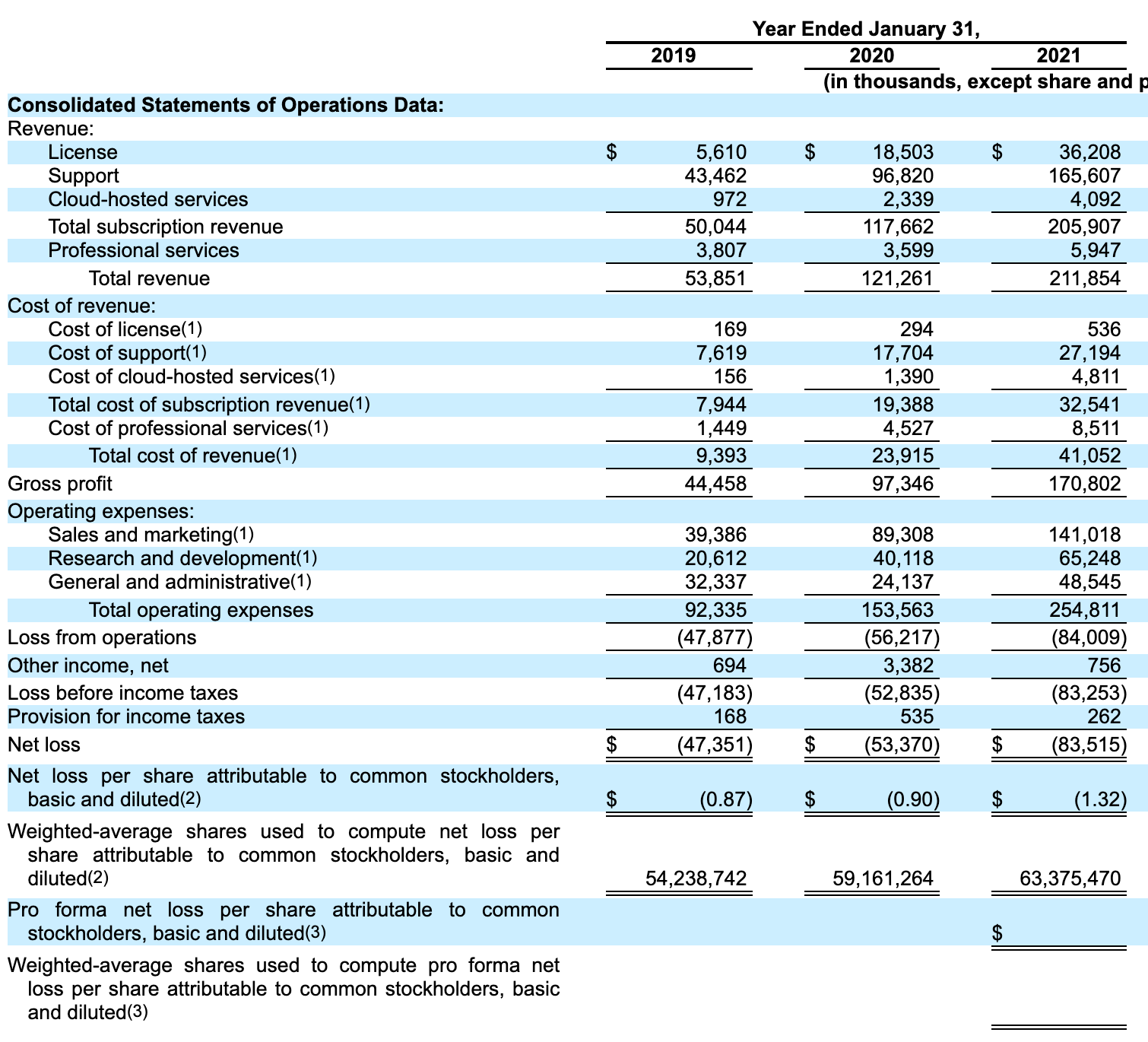

Finally, it’s worth taking a moment to dig into GAAP vs Non-GAAP. The Financial Accounting Standards Board defines the accounting rules known as GAAP, Generally Accepted Accounting Principles, and most financials you’ll see will label themselves as either GAAP compliant or not, for example this segment of HashiCorp’s 10-K statement.

There is little consistency in how companies calculate their non-GAAP financials, which makes them tricky to reason about. Most frequently, companies exclude non-recurring or one-time expenses. Assuming you’re looking at your company’s internal P&L, the best bet is to ask someone on your Finance team to explicitly walk you through how any non-GAAP figures differ from the GAAP definition. Often non-GAAP gives a clearer understanding of a business’ operational state, but the goal of any non-GAAP measure is always crafting a narrative: make sure you understand the motivations behind that narrative!

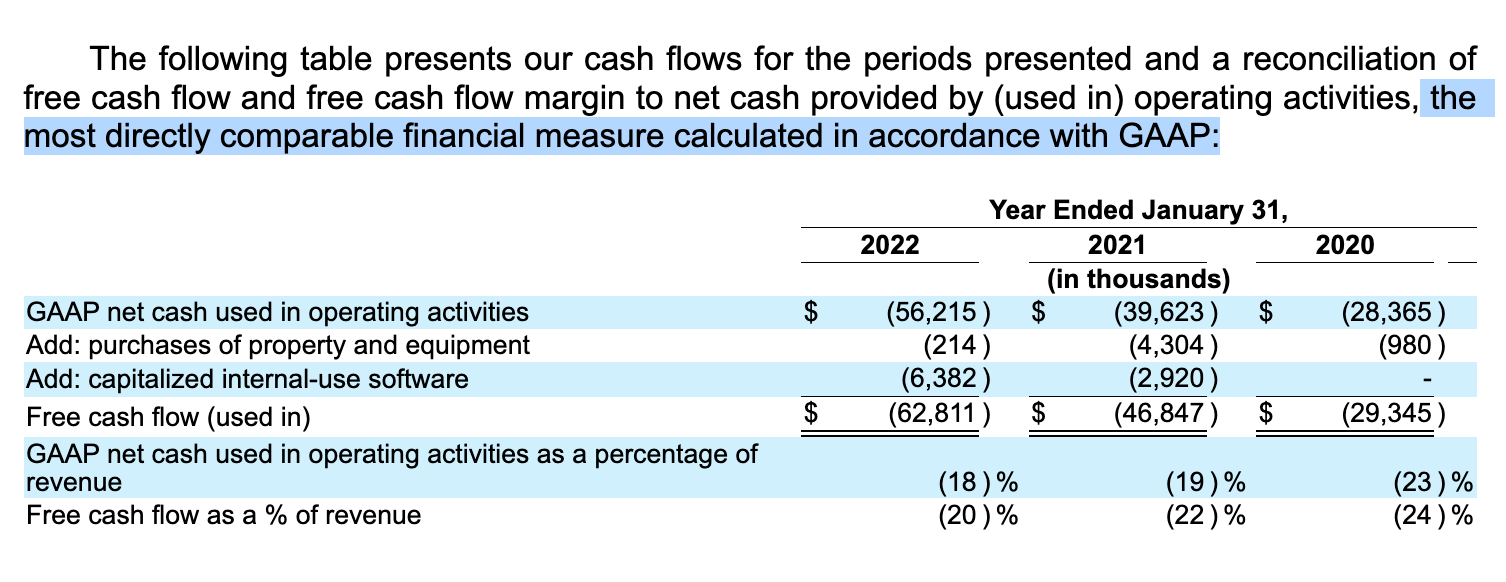

Learning from a P&L

Now that we’ve covered the individual components of the P&L, let’s dig into actually analyzing it. The very first step to take is moving it into our own spreadsheet so we can do a bit of basic math, in this case using Google sheets. We’ll start with columns tracking year-over-year (YoY) growth.

Once you have a version of the table you can edit, the remaining steps I’d use to explore the statement are:

- understand relationship between revenue and cost of revenue, by business lines

- explore the delta between historical trend and forecast projections (if you’re looking at a private company’s P&L which includes with a forecast; this won’t apply for public data)

- write down what you find surprising

- identify further actions to understand those surprising areas

The final step we’ll handle once we’ve collected our questions. Before that, we’ll go through the table row by row and apply the first three steps, starting with revenue:

- License revenue grew by 230% (‘19-‘20) and then 96% (‘20-‘21)

- Support revenue grew by 123% (‘19-‘20) and then 71% (‘20-‘21)

- Cloud services revenue grew by 141% (‘19-‘20) and then 75% (‘20-‘21)

- Total revenue grew by 125% (‘19-‘20) and then 75% (‘20-‘21)

- My sense of cloud services is that they’re going at an OK clip, but a bit slower than expected given their absolute size (4m in 2021) is relatively low. Purely from a financial analysis perspective, I’d wonder if maybe cloud services don’t yet have a strong product-market fit or perhaps are having some go-to-market challenges.

- In addition to cloud services, professional services is also small and growing slowly

- Altogether, these are all reasonable revenue growth rates, particularly the support revenue growth is strong given the absolute size of the business

Another question for each of these business lines is what percentage of revenue is coming from renewing customers and what percentage is coming from new business? The core of a good SaaS business is a healthy renewal rate: you need a much smaller sales team to drive revenue growth if the product does a good job of retaining existing revenue.

Next, looking at “cost of revenue.” What’s really interesting is places where cost growth is accelerating or decelerating relative to revenue growth. For example, license revenue grew by 96% in ‘20 to ‘21 and costs grew a bit slower at 82% in that same period. This means they’re achieving some economies in their growth. Conversely, it will definitely be interesting to dig into cloud services revenue and costs, where revenue only grew 75% from ‘20 to ‘21 while costs grew 246%. Not understanding the strategic role of cloud services, the P&L doesn’t tell a particularly optimistic story about its trajectory.

Sometimes the interesting questions come from shifts over time, for example it’s interesting that growth in support costs outpaced support revenue growth in ‘20, but not in ‘21. Understanding why support costs grew more slowly in ‘21 than in ‘20 will lead to a valuable insight into how that business truly operates.

Looking at total revenue growth versus total cost of revenue growth, there’s a slightly concerning trend that revenue is growing slower than costs in ‘20 (155% vs 125%) and just barely faster than costs in ‘21 (75% vs 72%). However, this is a situation where looking at percentage growth is a bit misleading. The absolute values tell a much healthier story, as is made clear in the gross profit line with strong positives across the line.

Next up is operating expenses. Sales and marketing (S&M) spend accelerated a fair bit in ‘20 and then decelerated in ‘21 on a relative basis. However, on absolute basis S&M costs grew by about $50m both years. That’s a large increase and worth digging into where that spend is going. It’s often helpful to look at the relative size across operating sections, and I personally find it a bit surprising that “General and administration” (G&A) is a larger operating cost than “Research and development” (R&D) and would love to understand that a bit better.

Finally, a quick look at net loss. This is not a profitable business, and the loss is growing. However, losses grew more slowly than revenue growth in ‘21 and grew much slower than revenue growth in ‘20. Understanding what cused that swing (at least part of it was G&A costs doubling from ‘20 to ‘21) will make the path to profitability much clearer.

Digging into the questions

Alright, so let’s end by considering how we might dig into each of the surprising points (from the perspective of an internal executive). What I’ve found most effective is grouping the questions by team to follow up with, sending them your questions, and then scheduling time to discuss.

Questions to dig in with the finance team:

- What is revenue retention by business line? How much revenue is new versus renewing? (This might be a sales team question, depends a bit on company and structure.)

- Why were G&A operating costs higher than R&D operating costs in ‘19? Why did G&A costs double from ‘20 to ‘21?

Questions to ask appropriate business owners:

- Why is cloud services growing relatively slowly? (talk to product and sales teams)

- Why are cloud services costs growing 3.5x faster than revenue? Do we expect that to no longer be true at some point in the future?

- Why did growth in support costs grow faster than support revenue growth in ‘21 but not in ‘20? What changed?

- What is the additional $50m S&M spend in both ‘20 and ‘21 going towards? How are we measuring efficiency of that spend?

Questions that should be answered by your management team’s strategy:

- What is path to profitability?

- What is our strategy around S&M operating costs versus R&D operating costs?

After having these discussions, you will have a vastly clearer understanding of your business’ reality. Before running an exercise like this, you may think that you understand your business, but you were relying on other folks’ interpretation for fuel that understanding. Now it’s your understanding driving your confidence.

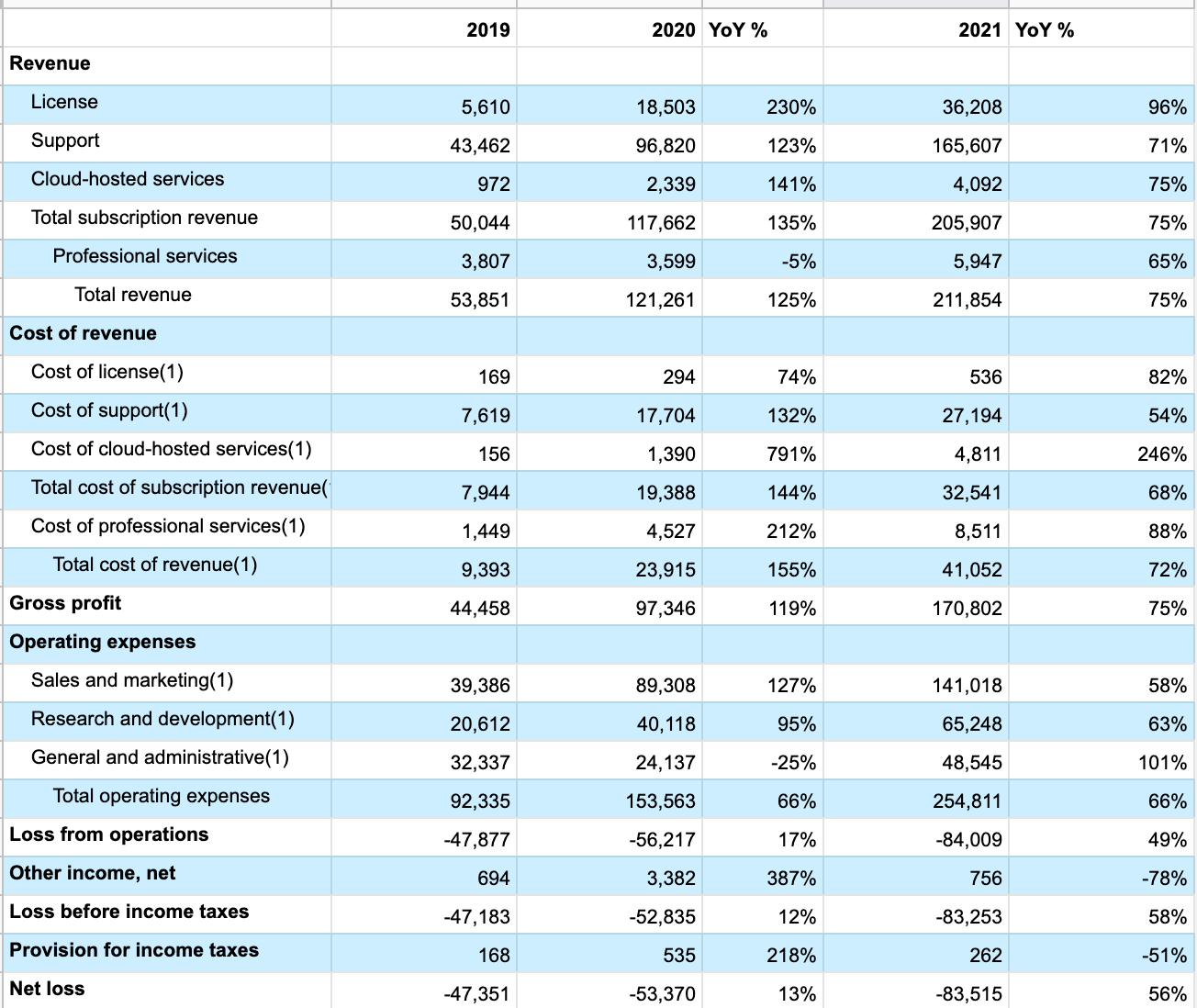

This is an ongoing activity

After you dig through P&L, you might imagine that you’re done. That’s true in a discrete sense, but really your understanding is merely paused until the next iteration of the P&L becomes available. For example, we reviewed HashiCorp’s S-1 which includes their performance through January, 2021. They shared results through January, 2022 in their 10-K issued in March, 2022. On page 77, they have their 2022 results (meaning specifically, results through January, 2022).

I won’t go into the full details, but if you review this spreadsheet combining their S-1 and 10-K results, you can tell they had a challenging year. HashiCorp is far from alone in that regard, almost everyone is having a rough year, but if they rise to this challenge, then they might come out of this adversity as a much more profitable company. This uncertainty is a bit part of why I don’t generally recommend folks try to make financially optimal moves during a downturn.

Finding S-1 and 10-Ks

A brief tangent on finding P&L statements for public companies. All the numbers shared in this piece are public record, and you can find them by going to Securities and Exchange Comission’s EDGAR search and typing in the companies name. Using HashiCorp for an example, I started typing in “hashi” after which search suggested HashiCorp’s ticker, “HCP”, and I clicked to HashiCorp, Inc’s page. From there click on “View filings” and you can see all the interesting filings, particularly the S-1 and 10-Ks.

Most companies will also have an investor relations (IR) website, like HashiCorp’s ir.hashicorp.com with links to their recent filings like this page hosting HashiCorp’s quarterly results. Generally, it’s easier to use EDGAR, but an IR website will often espouse the company’s preferred narrative through their earnings calls and press releases. Even if you do want to understand the company’s preferred narrative, I’d recommend reading their P&L without any narrative first to avoid unduly steering your attention in their preferred direction.

As a closing thought, P&Ls at early stage companies are often wrong, and they can be wrong in a lot of different ways. Costs can be miscategorized, non-recurring revenue can be booked as recurring revenue, etc. However, even when a P&L is wrong, it’s almost always wrong in an interesting way that will teach you about the underlying business and team running it. If you really want to understand a business starting from scratch, there are few better starting places than their latest P&L statement.