Productivity in the age of hypergrowth.

You don’t hear the term hypergrowth quite as much as you did a couple years ago. Sure, you might hear it any given week, but you might open up Techmeme and not see it, which is a monumental return to a kinder, gentler past. (Or perhaps we’re just unicorning now.)

Fortunately for engineering managers everywhere, the challenges of managing in quickly growing companies still very much exist.

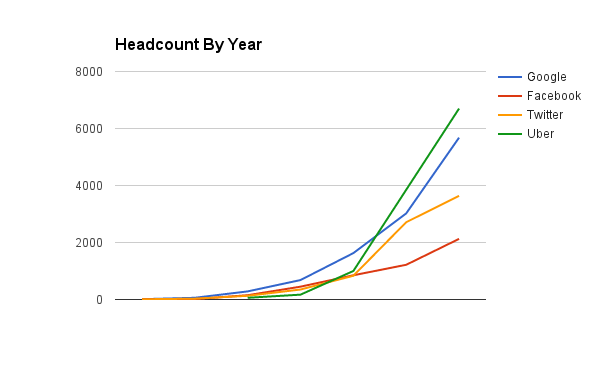

When I started at Uber, we were almost 1,000 employees and doubling headcount every six months. An old-timer summarized their experience as:

We’re growing so quickly, that every six months we’re a new company.

A bystander quickly added a corollary:

Which means our process is always six months behind our headcount.

Helping your team be successful when defunct process merges with a constant influx of new engineers and system load has been one of the most rewarding opportunities I’ve had in my career, and this is an attempt to explore the challenges and some strategies I’ve seen for mitigating and overcoming them.

More engineers, more problems

All real-world systems have some degree of inherent self-healing properties: an overloaded database will slow down enough that someone fixes it, overwhelmed employees will get slow at finishing work until someone finds a way to help.

Very few real-world systems have efficient and deliberate self-healing properties, and this is where things get exciting as you double engineers and customers year over year over year.

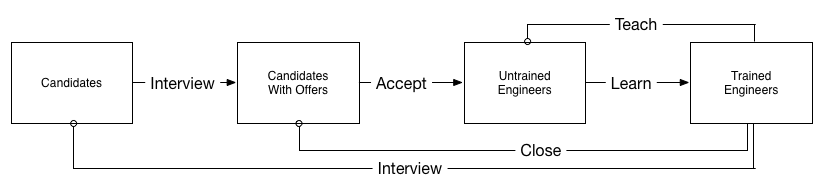

Productively integrating large numbers of engineers is hard.

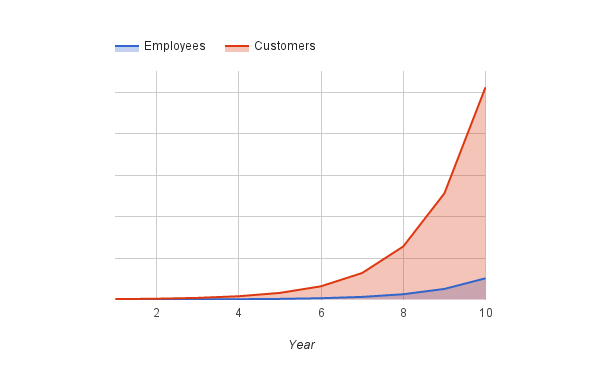

Just how challenging depends on how quickly you can ramp engineers up to self-sufficient productivity, but if you’re doubling every six months and it takes six to twelve months to ramp up, then you can quickly find a scenario where untrained engineers increasing outnumber the trained engineers, and each trained engineer is devoting much of their time to training a couple of newer engineers.

Imagine a scenario where:

- training takes about ten hours per week from each trained engineer,

- untrained engineers are 1/3rd as productive as trained engineers,

and you reach the above chart’s (admittedly, pretty worst-case

scenario) ratio of two untrained to one trained.

Worse, for those three people you’re only getting the productivity of 1.16 trained engineers

(2 * .33 for the untrained engineers plus .5 * 1 for the trainer).

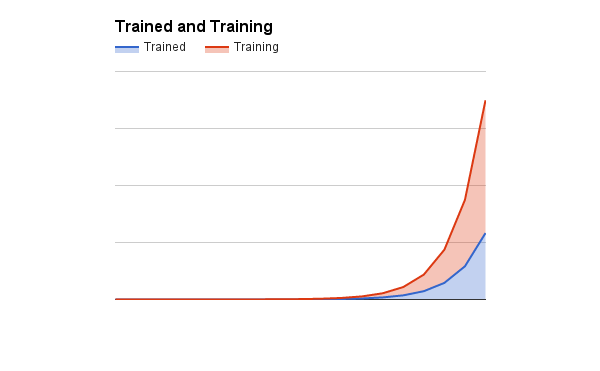

You also need to factor in the time spent on hiring.

If you’re trying to double every six months, and about ten percent of candidates undertaking phone screens eventually join, then you need to do ten interviews per existing engineer in that time period, with each interview taking about two hours to prep, perform and debrief.

That’s only four hours per month if you

can leverage your entire existing team, but training comes up again here: if it takes you

six months to get the average engineer onto your interview loop, each trained engineer is now

doing three to four hours of hiring related work a week, and your trained engineers are down to 0.4 efficiency.

The overall team is getting 1.06 engineers of work out of every three engineers.

It’s not just training and hiring though:

- For every additional order of magnitude of engineers you need to design and maintain a new layer of management.

- For every ~10 engineers you need an additional team, which requires more coordination.

- Each engineer means more commits and deployments per day, creating load on your development tools.

- Most outages are caused by deployments, so more deployments drive more outages, which in turn require incident management, mitigations and postmortems.

- More engineers lead to more specialized teams and systems, which require increasingly small oncall rotations for your oncall engineers to have enough system context to debug and resolve production issues, so relative time invested in oncall goes up.

Let’s do a bit more handwavy math to factor these in.

Only your trained engineers can go oncall, they’re oncall one week a month, and are busy about

half their time oncall. So that’s a total impact of five hours per week for your trained engineers, who

are now down to 0.275 efficiency, and your team overall is now getting less than the output

of a single trained engineer for every three engineers you’ve hired.

(This is admittedly an unfair comparison because it’s not accounting for the oncall load on the smaller initial teams, but if you accept the premise that oncall load grows as engineer headcount grows and load grows as the number of rotation grows, then the conclusion should still roughly hold.)

Although it’s rarely quite this extreme, this is where the oft raised concern that hiring is slowing us down comes from: at high enough rates, the marginal added value of hiring gets very slow, especially if your training process is weak.

Sometimes very low means negative!

Systems survive one magnitude of growth

We’ve looked a bit at productivity’s tortured relationship with engineering headcount, so now let’s also think a bit about how the load on your systems is growing.

Understanding the overall impact of increased load comes down to a few important trends:

- Most system implemented systems are designed to support one to two orders magnitude of growth from current load. Even systems designed for more growth tend to run into limitations within one to two order of magnitude.

- If your traffic doubles every six months, then your load increases an order of magnitude every eighteen months. (And sometimes new features or products cause load to increase much more quickly.)

- The cardinality of supported systems increases over time as you add teams, and as “trivial” systems go from unsupported afterthoughts to focal points of entire teams as they reach scaling plateaus (things like Kafka, mail delivery, Redis, etc).

If your company is designing systems to last one order of magnitude and doubling every six months, then you’ll have to reimplement every system twice every three years. This creates a great deal of risk–almost every platform team is working on a critical scaling project–and can also creates a great deal of resource contention to finish these concurrent rewrites.

However, the real productivity killer is not system rewrites, but the migrations which follow those rewrites. Poorly designed migrations expand the consequences of this rewrite loop from the individual teams supporting the systems to the entire surrounding organization.

If each migration takes a week, each team is eight engineers, and you’re doing four migrations a year, then you’re losing about 1% of your company’s total productivity. If each of those migrations takes closer to a month, or if they are only possible for your small cadre of trained engineers whose time is already tightly contended for, then the impact becomes far more pronounced.

There is a lot more that could be said here–companies that mature rapidly often have tight and urgent deadlines around moving to multiple datacenters, to active-active designs, to new international regions and other critical projects–but I think we’ve covered our bases on how increasing system load can become a drag on overall engineering throughput.

The real question is, what do we do about any of this?

Ways to manage entropy

My favorite observation from The Phoenix Project is that you only get value from projects when they finish: to make progress, above all else, you must ensure that some of your projects finish.

That might imply that there is an easy solution, but finishing projects is pretty hard when most of your time is consumed by other demands.

Let’s tackle hiring first, as hiring and training are often a team’s biggest time investment.

When your company has decided it is going to grow, you cannot stop it from growing, but on the other hand you absolutely can concentrate that growth, such that your teams alternate between periods of rapid hiring and periods of consolidation and gelling. Most teams work best when scoped to approximately eight engineers, so as each team gets to that point, you can move the hiring spigot to another team (or to a new team). As the post-hiring team gels, eventually the entire group will be trained and able to push projects forward.

You can do something similar on an individual basis, rotating engineers off of interviewing periodically to give them time to recouperate. With high interview loads, you’ll sometimes notice last year’s solid interviewer giving a poor candidate experience or rejecting every incoming candidate. If they’re doing more than three interviews a week, it is a useful act of mercy to give them a month off every three or four months.

I have less evidence of how to tackle the training component of this, but generally you start to see larger companies do major investments into both new-hire bootcamps and recurring education class.

I’m optimistically confident that we’re not entirely cargo-culting this idea from each other, so it probably works, but I hope to get an opportunity to spend more time understanding how effective those programs can be. If you could get training down to four weeks, imagine how quickly you could hire without overwhelming the existing team!

The second most effective time thief I’ve found is adhoc interruptions: getting pinged on HipChat or Slack, taps on the shoulder, alerts from your oncall system, high-volume email lists and so on.

The strategy here is to funnel interrupts into an increasingly small surface area, and then automate that surface area as much as possible. Asking people to file tickets, creating chatbots which automate filing tickets, creating a service cookbook, and so on.

With that setup in place, create a rotation for people who are available to answer questions, and train your team not to answer other forms of interrupts. This is remarkably uncomfortable because we want to be helpful humans, but becomes necessary as the number of interrupts climb higher.

One specific tool that I’ve found extremely helpful here is an ownership registry which allows you to look up who owns what, eliminating the frequent “who owns X?” variety of question. You’ll need this sort of thing to automate paging the right oncall rotation, so might as well get two useful tools out of it!

A similar variant of this is adhoc meeting requests. The best tool I’ve found for this is to block out a few large blocks of time each week to focus. This can range from working from home on Thursday, to blocking out Monday and Wednesday afternoons, to blocking out from eight to eleven each morning. Experiment a bit and find something that works well for you.

Finally, the one thing I’ve found at companies with very few interrupts and almost nowhere else: really great, consistently available documentation. It’s probably even harder to bootstrap documentation into a non-documenting company than it is to bootstrap unittests into a non-testing company, but the best solution to frequent interruptions I’ve seen is a culture of documentation, documentation reading, and a documentation search that actually works.

There are a non-zero number of companies which do internal documentation well, but I’m less sure if there are a non-zero number of companies with more than twenty engineers who do this well. If you know any, please let me know so I can pick their brains.

In my opinion, probably the most important opportunity is designing your software to be flexible. I’ve described this as “fail open and layer policy”; the best system rewrite is the one that didn’t happen, and if you can avoid baking in arbitrary policy decisions which will change frequently over time, then you are much more likely to be able to keep using a system for the long term.

If you’re going to have to rewrite your systems every few years due to increased scale, let’s avoid any unnecessary rewrites, ya know?

Along these lines, if you can keep your interfaces generic, then you are able to skip the migration phase of system reimplementation, which is tends to be the longest and trickiest phase, and can iterate much more quickly and maintain fewer concurrent versions. There is absolutely a cost to maintaining this extra layer of indirection, but if you’ve already rewritten a system twice, take the time to abstract the interface as part of the third rewrite and thank yourself later (by the time you’d do the fourth rewrite you’d be dealing with migrating six times the engineers).

Finally, a related antipattern is the gatekeeper pattern. Having humans who perform gatekeeping activities creates very odd social dynamics, and is rarely a great use of a human’s time. When at all possible, build systems with sufficient isolation that you can allow most actions to go forward and when they do occasion to fail, make sure they fail with a limited blast radius.

There are some cases where gatekeepers are necessary for legal or compliance reasons, or because a system is deeply frail, but I think we should generally treat gatekeeping as a significant implementation bug rather than a stability feature to be emulated.

Closing thoughts

None of the ideas here are instant wins. It’s my sense that managing rapid growth is more along the lines of stacking small wins than identifying silver bullets. I have used all of these techniques, and am using most of them today to some extent or another, so hopefully they will at least give you a few ideas.

Something that is somewhat ignored a bit here is how to handle urgent projects requests when you’re already underwater with your existing work and maintenance. The most valuable skill there is learning to say no in a way that is appropriate to your company’s culture, which probably deserves it’s own article. There are probably some companies where saying no is culturally impossible, and in those places I guess you either learn to say your no’s as yes’s or maybe you find a slightly easier environment to participate in.

How do you remain productive in times of hypergrowth?