Designations, levels and calibrations.

The most sacred responsibilities of management are selecting your company’s role model, identifying who to promote, and deciding who needs to leave. At small companies these decisions tend to be fairly ad-hoc, but as companies grow, these decisions solidify into a formal performance management system. Many managers try to engage with these systems as little as possible, which is a shame. If you want to shape your company’s culture, inclusion or performance, this is your most valuable entry point.

The number of approaches to performance management is uncountably vast, but most of them are composed of three elements:

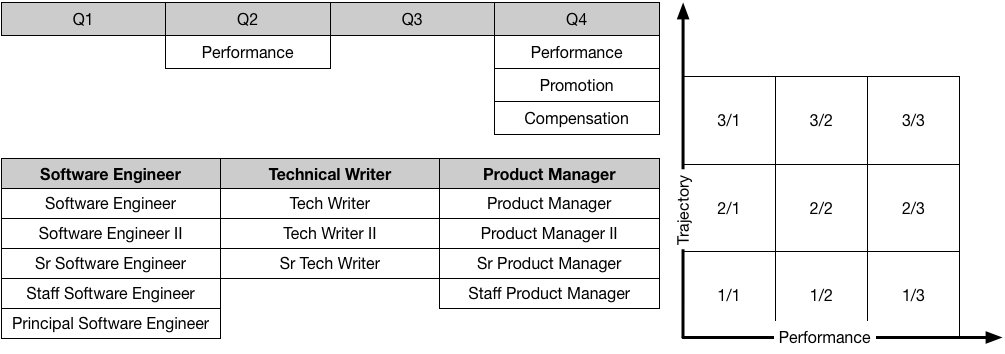

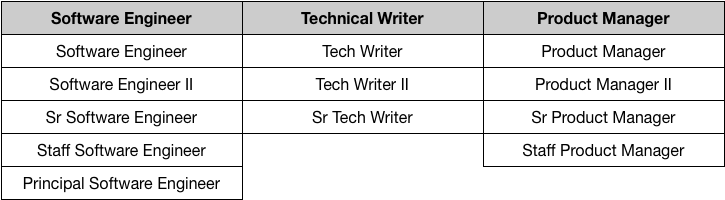

- Career ladders describe the expected evolution an individual will take in their job. For example, a software engineer ladder might describe expectations of a Software Engineer, a Software Engineer II, a Senior Software Engineer, and a Staff Engineer.

- Performance designations which rate individuals’ performance for a given period against the expectations of their ladder and level.

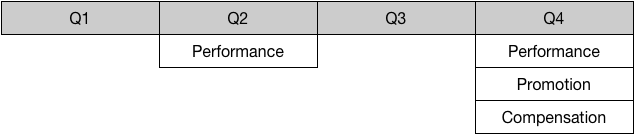

- Performance cycles which occur once, twice or four times a year, with the goal of assigning consistent performance designations.

The purpose of these combined systems is to focus the company’s efforts towards activities that help the company succeed. The output of these efforts is to provide explicit feedback to employees on how the company is valuing their work.

Career ladders

At the foundation of an effective performance management system are career ladders, which describe the expected behaviors and responsibilities for a role. There is significant overhead to each career ladder that you write and maintain, amd also significant downside to attempting to group different roles onto a shared ladder.

What I’ve seen work best is to be tolerant of career ladder proliferation–really try to make a ladder for each unique role–but to only invest significant time in refining any given ladder as it becomes applicable for more folks. As a rule of thumb, any ladder with more than ten folks should probably be fully fleshed out, but smaller functions can probably survive with something rough. This works particularly well if you extend an open invitation to folks in that role to improve their ladder! (As an aside, I strongly recommend writing a lightweight ladder before you hiring the first person into a given role. The alternatives tend to work out poorly.)

One effective method for reducing the fixed cost of maintaining ladders is to establish a template and shared themes across every ladder. Not only does this reduces fixed maintenance costs and it also focuses the company on a set of common values.

Each ladder is composed of levels, which describe how the role evolves in responsibility and complexity as the practitioner becomes more senior. The number of levels appropriate will vary across ladders, function size, and function age. Most companies seem to start with three levels and slowly add levels over time, perhaps adding one every two years. At each level, you’ll want to specify the expectations across each of your values. Crisp level boundaries reduce ambiguity when considering whether to promote an individual across levels.

Crisp boundaries are also important as they provide folks within a ladder a useful mental model of where they are in their journey, who their peers are, and who they should view as role models. The level definitions are quite effective at defining the behaviors you’ll want in your role models, which are the behaviors you’ll see everywhere a year or two later.

A good ladder allows folks to accurately self-access, self-contained and short. A bad ladder is ambiguous and requires deep knowledge of precedent to apply correctly. If there is one component of performance management that you’re going to invest into doing well, make it the ladders: everything else builds on this foundation.

Performance designations

Once you have the career ladders written, the next step is to start applying it. The most frequent application will be using it as a guide for self-reflection and during career coaching 1:1s, but you’ll also want to create formal feedback into the form of a performance designation.

Performance designations are an explicit statement of how an individual is performing against the expectations of their career ladder at their current level over a particular period of time. Because they are explicit, they are a backstop against miscommunication between the company and an employee, but it is cause of concern and debugging if the explicit designation doesn’t match with the implicit signals someone has received.

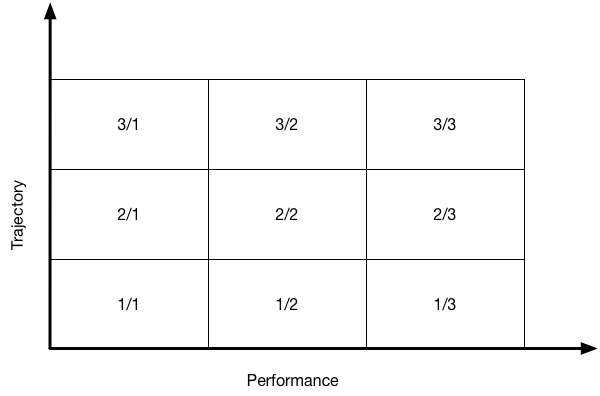

Most companies start out using a single scale to represent performance designations, often whole numbers from one to five. Over time these often move towards the “nine-blocker” format, a three-by-three grid with one axis representing performance and the other representing trajectory. Having used a number of systems, I prefer to use the simplest representation possible. The extra knobs in more complicated systems support more granularity, but my sense is that they do more to create the impression of rigor while remaining equally challenging to implement in a consistent, fair way.

More important than the scale used for rating, is how the ratings are calculated. The typical setup is:

- Self-review is written by the individual receiving the designation. The best formats try to explicitly compare and contrast against their appropriate ladder and level. I’ve also seen good success in the “brag document” format.

- Peer reviews are written by an individual’s peers, and are useful for recognizing mentorship and leadership contributions that might otherwise get missed. Structured properly, they are also useful for identifying problems that you’re missing out on, but generally peers are not comfortable providing negative feedback.

- Upward review are used to ensure managers’ performance includes the perspective of the folks they manage directly. Format is similar to peer review.

- Manager review is written by an individual’s manager, typically a synthesis of the self, peer and upward reviews.

From those four sets of reviews, a provisional designation is established, which is used as an input to a calibration system. Calibrations are rounds of reviewing performance designations and reviews, with the aim of ensuring ratings are consistent and fair across teams, organizations and the company overall.

A standard calibration system will happen at each level of the organizational tree. It’s pretty challenging to strike the balance between avoiding calibration fatigue from many sessions and ensuring folks doing the calibration are familiar with the work they are calibrating. Promotions are typically also considered during the calibration process.

Calibrations fall soundly in the unenviable category of things which are terrible but without obvious replacement. Done poorly, they become bastions of bias and fiercely political, but they’re pretty hard to do well even when everyone is well meaning! Some rules that I’ve found useful for calibrations:

- Shared quest for consistency. Try to frame calibration sessions as a community of folks working together towards the correct designations. Steer folks away from anchoring on the designations they enter with, and toward shared inquiry. Doing this well requires a great deal of psychological safety among calibrators, which needs to be cultivated long before they enter the room.

- Read, don’t present. Many calibration systems depend heavily on whether managers are effective, concise presenters, which can become a larger factor in an individual’s designation than their own work. Don’t allow folks to pitch their candidates in the room, but instead have folks read the manager review. This still depends on the manager’s preparation, but it reduces the pressure to perform in the calibration session itself.

- Compare against ladder, not against others. Comparing folks against each other tends to introduce false equivalencies without adding much clarity. Focus on the ladder instead.

- Study the distribution, don’t enforce it. Historically many companies fit designations to a fixed curve, often referred to stack ranking. Stack ranking is a terrible solution, but the problem it tries to address: it’s easy for the meaning of a given designation to skew as a company grows. Instead of fitting to a distribution, I find it useful to review the distributions across different organizations and to discuss why they appear to be deviating. Are the organizations performing at meaningfully different levels, or have meanings skewed?

Somewhat unexpectedly, performance designations are usually not meant to be the primary mechanism for handling poor performance: feedback for weak performance should be delivered immediately. Waiting for performance designations to deal with performance issues is typically a sign of managerial avoidance. That said, it does serve as an effective backstop for ensuring these kinds of issues are being addressed.

Performance cycles

Once you have career ladders and performance designations defined, you need a process to ensure designations are being periodically calculated in a consistent and fair fashion, that process is your performance cycle.

Most companies do either annual or bi-annual performance cycles, although it’s not unheard of to do them quarterly. The overhead of running a cycle tends to be fairly heavy, which leads folks to do them less frequently. Conversely, the feedback from the cycle tends to be very important, and a primary input into factors that folks care about a great deal like compensation, so there is also countervailing pressure to do them frequently.

The most important factor I’ve seen for effective performance cycles is forcing folks to practice. Providing well structure timelines is very helpful, particularly if they’re concise, but there tend to be so many competing demands that folks do the most minimal skimming they can get away with.

Having teams do a practice round, at least for new managers or after the cycle has been modified, is the only effective way I’ve found to get around this. You can often direct this practice as an opportunity for folks to get feedback on their self-reviews, ensuring that folks find it useful, even if they’re initially skeptical.

Finally, there is an interesting tension between improving the cycle as quickly as possible and allow the cycle to stabilize so that people can get good at it. My sense is that you want to change the cycle at most once every second time. This lets folks adapt fully, and also gives you enough time to observe how well changes work.

This is a small survey of some of the basics of designing performance management systems, and there is much, much more out there. It’s valuable to start from the common structures that most companies adapt, but don’t fall captive to them! Many of these systems are relatively recent inventions, and take a particular, peculiar view of the ideal relationship between an employee and the company they work at.

If you’re looking for more, I’ve written about several special topics in performance systems, and Laszlo Bock’s Work Rules is a good read.