Path to engineering manager of managers.

Not very polished, but I’m giving a short talk about the path to engineering manager of managers roles, and these are my notes.

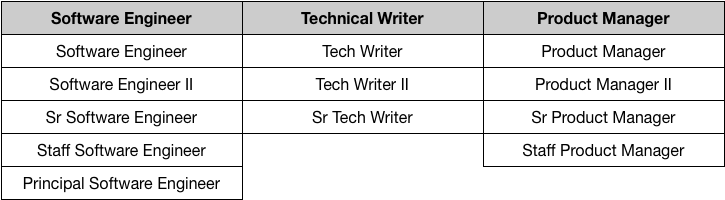

Once your company gets large enough to roll out a formal career ladder, it becomes the foundation of most discussions about performance and promotion.

All ladders have certain requirements that have to be met in order to advance, but typically the resources required to fulfill those requirements aren’t scarce. As you get more senior, scarcity starts to creep in:

- How many “staff”-level engineering projects are available this cycle?

- How many folks can deeply influence organizational direction?

- How many folks can lead the team’s project for this quarter?

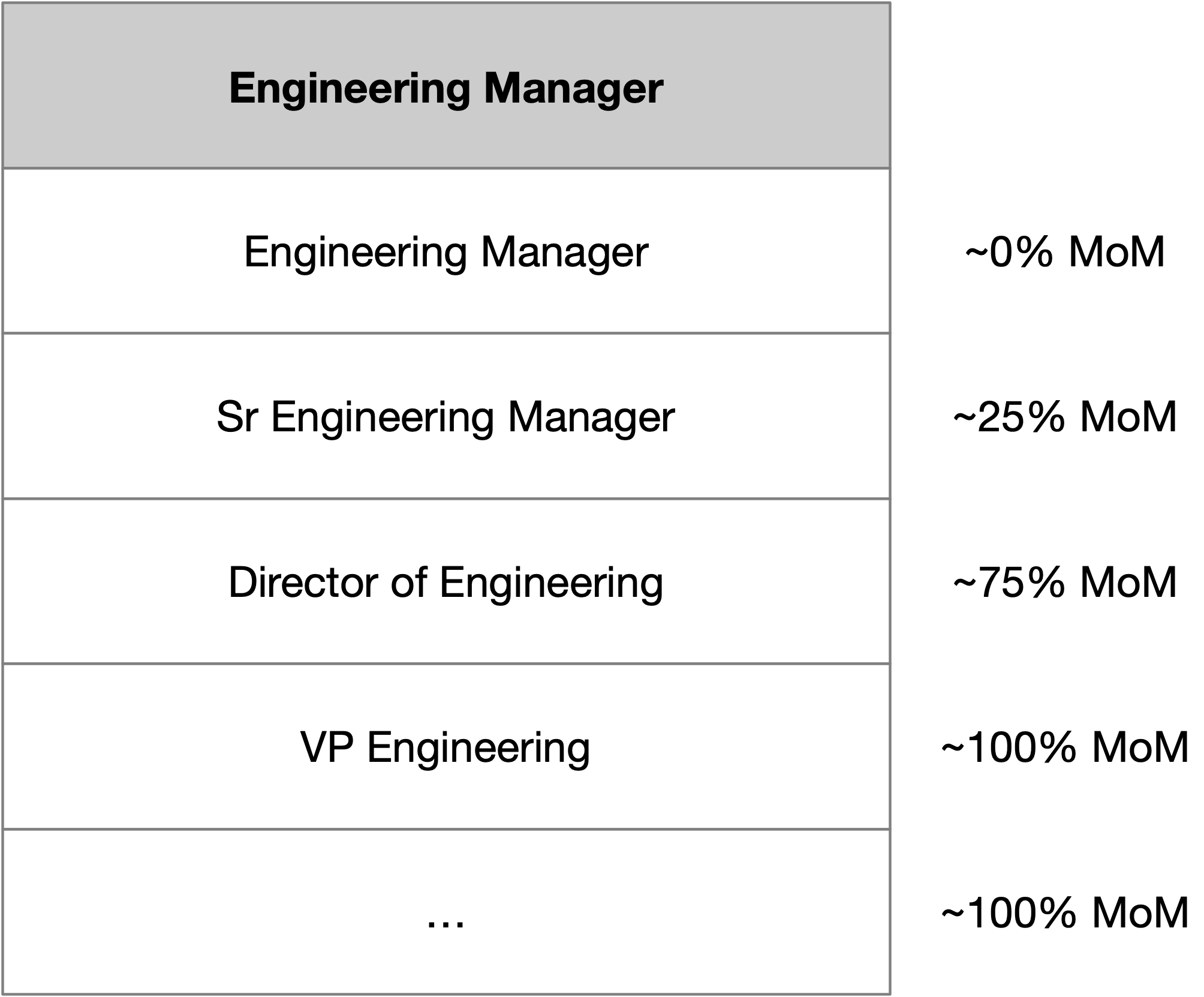

The boon and curse of most scarce resources is that there is a great deal of room for interpretation – maybe it really was a staff project – but managers often run into a particularly difficult scarce resource: they have to start managing managers to advance in their role.

This is a well-known anti-pattern to ladder writers, so it’s an interesting phenomenon that every company is very deliberate to avoid codifying “managing managers” – or even team size – into their ladder requirements, but most folks in most companies end up believing that it’s an implicit requirement.

It’s pretty easy to understand why: it’s not explicit anywhere, but pretty much everyone past a certain point is managing managers. To get there, it feels like you have to follow.

Challenging this assumption a bit, you do not have to become a manager of managers to continue advancing your impact or your career. There are real, senior management and leadership roles that don’t require that switch, but they typically (a) exist at either very large or very small companies, (b) tend to rely more on subject-matter expertise in a critical but adjacent topic (e.g. for a product oriented company, that might be managing infrastructure costs or reliability), and finally (c) they’re quite a bit less common and might not exist at your company.

If the existing manager of manager roles at your company aren’t the right fit, this is a place where you can really flex your career narrative. Find ways to develop yourself and increase your impact, and then partner with your management team to translate that into your ladder. Remember, your ladder was almost certainly carefully crafted with the intention of this being possible, and folks love to set a positive precedent that things which appear impossible are possible.

But maybe you really do want to move into a manager of managers role, and it’s not just because you “have” to, it’s what you’re interested in. How do you get one?

There are only really three paths to your first manager of managers role:

- Replace an existing role because someone leaves your company.

- Fill a new role created by your company growing (e.g. participate in the managerial pyramid scheme of hypergrowth).

- Get hired by a different company into the role.

My decision to join Uber in 2015 was a very deliberate decision to find a company where I could develop from managing a small team to a larger one. I’d found getting hired directly as a manager of managers was quite difficult without the existing experience, and in retrospect I’m very glad I was able to make this particular transition while operating in an environment with enough structure and other folks operating in the same sorts of roles that I could learn from and with.

I’ve seen folks successfully take all three of these paths, but the second is the path I’ve seen work the most consistently. As such, the single most effective thing you can do is to join a company that is growing fairly quickly.

Any quick growing company isn’t enough though, it’s also much easier when you join a company that has a structured process to consider internal candidates. Allowing qualified internal candidates to participate in such searches is something we’ve done more and more at Stripe as we’ve grown, and is something I’m quite proud of.

Another side-effect is that you get much better feedback when you interview internally. Internally, you’ll generally get thoughtful written feedback for you to learn from. For external interviews, most companies just won’t give you very structured feedback out of an abundance of legal caution.

That’s not to say that process isn’t sometimes quite awkward – to the contrary, it can create some delightfully weird professional situations, but I think it’s still the best approach thing.

A really interesting thing happens, though, when you get to a standardized process for considering internal candidates within your interview loops, which is that now there is a single path to getting these sorts of roles – pass an interview loop for a manager of manager role.

That’s a more concrete problem to focus on, and the question then becomes “how do interview loops for manager of managers roles work?”

The basics are going to be roughly the same – a phone screen, a couple of onsites, some reference checks – but the skills being evaluated will generally differ quite a bit.

You will, at times, find yourself being interviewed for a manager of managers position through a general engineering manager loop (the same as you might for a non-manager of managers role), and you might even find some very small companies that primarily evaluate you as a senior developer… and I don’t have much advice here for those scenarios.

Or perhaps the advice is to ask yourself if you’re motivated to do the teaching and growing of the organization that those choice suggest will be a big part of your upcoming work.

A good manager of managers loop is going to focus more on:

communication - are you able to communicate a business topic to a technical audience? Communicate a technical constraint to a business audience where they come away understanding the tradeoff? Can you summarize a nuanced, complex topic concretely? Can you explain tradeoffs clearly, showing understanding of all perspectives?

leading at scale - many leadership techniques don’t work well when you’re only able to devote 10-20% of your time to an area, have you developed compensating set of skills to remain effective in such scenarios? Things like coaching, effective goals, strategy and vision become your core toolkit. A good process tests how these components intersect, for example having you coach someone on their goals, as well as writing a strategy along with identifying the short and long-term goals to support that strategy.

operating at scale - have you operated an organization? This will focus on topics like scaling the hiring process, succession plannining, evolving and using performance management systems. Are you an effective hiring manager, including for roles that you haven’t personally performed (will you be able to hire senior candidates to work on your team)? Are you able to read an organizational health report and action it effectively? Are you familiar with typical organization evolution issues and rough edges like the friction around career levels?

good partner - are you a collaborative, effective partner to other teams and functions? Do you have a non-hierarchical world view across functions? Do you understand how your function impacts other functions, and are willing to optimize globally rather than for your function?

domain expertise - do you have experience to be the functional leader for the area you’re joining? Are you familiar with the domain’s evolution and where it’s evolving next? Do you have thoughtful opinions and are willing to be challenged on those opinions (without becoming defensive)? This varies a bit by company. with some expecting their senior management to be domain specialists with a history of operating, and others being more comfortable with general management experience.

The most interesting thing is that you can almost certainly practice all of those in your current role. You absolutely do not need to be in a manager of managers role to build these skills, but you do need to be deliberate about selecting the projects that will fill in your personal gaps.

As you build up your skills, periodically apply to different roles – internally if available but otherwise externally – and get more feedback. Take that feedback and focus for the next set of projects.

Not discussed here, but once you do get into these sort of roles, you need to be pretty deliberate about staying in them. Particularly, to ensure that you’re scaling yourself inline with the company’s growth.

The intended audience for this talk is folks at a rapidly growing company who are likely to have access to manager of manager roles within their company, which means that it doesn’t address what can be the most pressing question for folks who aren’t in such situations: how do you get access to these roles to begin with?

It’s pretty difficult.