Operational mechanisms for strategy.

Even the best policies fail if they aren’t adopted by the teams they’re intended to serve. Can we persistently change our company’s behaviors with a one-time announcement? No, probably not.

I refer to the art of making policies work as “operations” or “strategy operations.” The good news is that effectively operating a policy is two-thirds avoiding common practices that simply don’t work. The other one-third takes some repetition, but can be practiced in any engineering role: there’s no need to wait until you’re an executive to start building mastery.

This chapter will dig into those mechanisms, with particular focus on:

- How policies are supported by operations, and how operations are composed of mechanisms that ensure they work well

- Evaluating operational mechanisms to select between different options, and determine which mechanisms are unlikely to be an effective choice

- Composing an operational plan for the specific set of policies that you are looking to support

- Common varieties of effective mechanisms such as approval forums, inspection mechanisms, nudges, and so on. We’ll also explore the sorts of mechanisms that tend to work poorly

- How to adjust your approach to operations if you are in an engineering role rather than an executive role

- How cargo-culting remains the largest threat to effective strategy operations

Let’s unpack the details of turning your potentially good policy into an impactful policy.

This is a chapter from Crafting Engineering Strategy.

What are operational mechanisms?

Operations are how a policy is implemented and reinforced. Effective operations ensure that your policies actually accomplish something. They can range from a recurring weekly meeting, to an alert that notifies the team when a threshold is exceeded, to a promotion rubric requiring a certain behavior to be promoted.

In the strategy for working with new private equity ownership, we introduce a policy to backfill hires at a lower level, and also limit the maximum number of principal engineers:

We will move to an “N-1” backfill policy, where departures are backfilled with a less senior level. We will also institute a strict maximum of one Principal Engineer per business unit, with any exceptions approved in writing by the CTO–this applies for both promotions and external hires.

That introduces an explicit operational mechanism of escalations going to the CTO, but it also introduces an implicit and undefined mechanism: how do we ensure the backfills are actually down-leveled as the policy instructs? It might be a group chat with engineering recruiting where the CTO approves the level of backfilled roles. Instead, it might be the responsibility of recruiting to enforce that downleveling. In a third approach, it might be taken on trust that hiring managers will do the right thing. Each of those three scenarios is a potential operational solution to implementing this policy. Operations is picking the right one for your circumstances, and then tweaking it as you learn from running it.

Operations in government

For another interesting take on how critical operations are, Recoding America by Jennifer Pahlka is well worth the read. It explores how well-intended government legislation often isn’t implementable, which results in policies that require massive IT investments but provide little benefit to constituents.

How to evaluate mechanisms

In order to determine the most effective operational mechanisms for the problems you’re working on, it’s useful to have a standardized rubric for evaluating mechanisms. While this rubric isn’t perfectly universal–customize it for your needs–having any rubric will make it easier to evaluate your options consistently.

The rubric I use to evaluate whether an operational mechanism will be effective is:

- Measurability: Can you measure both leading and lagging indicators to inspect the mechanism’s impact? If you have to choose between the two, measuring leading indicators allows much quicker evaluation and iteration on your mechanisms.

- Adoption cost: How much work will migrating to this mechanism require? Can this work be done incrementally or does it require a major, coordinated shift?

- User ease (or burden): After adopting this policy, how much easier (or harder) will it be for users to perform their work? If things will be harder, are those users able to tolerate the additional time?

- Provider ease (or burden): How much additional ongoing maintenance will this mechanism require from the centralized or platform team providing it? For example, if every new architecture proposal requires a thorough review by your Security team, does the Security team have the actual ability to support those reviews?

- Reliance on authority: How much does this mechanism depend on a top-down authority’s active support? If the sponsoring executive departs, will this mechanism remain effective? Is that an effective tradeoff in this case?

- Culturally aligned: Is this something that your organization is going to do, or something that they are going to fight against each step? Is there a way you can adjust the framing to make it more acceptable to your organization’s culture?

Generally, I find folks are good at evaluating mechanisms against these criteria, but somewhat worse at accepting the consequences of their evaluation. For example, falling in love with a particular mechanism and then trying to force the organization to accept a mechanism whose adoption cost is unbearably high, or introduce a mechanism that creates significant user burden onto a team that is already struggling with tight efficiency goals like a customer support team.

Self-awareness helps here, but so does consulting others to point out the errors in your reasoning, which is a core part of how I’ve found success in adopting operational mechanisms.

Composing an operational plan

Your operational plan is the sum of the mechanisms used to support your policies. While evaluating each individual mechanism in isolation is part of creating an operations plan, it’s also valuable to consider how the mechanisms will work together:

Review the policies you’ve developed. What sort of mechanisms seem most likely to support these policies? How might these mechanisms be pooled together to avoid redundancy?

Review the operational mechanisms that have worked in your organization. What mechanisms have been used to best effect, and which have left a sufficiently bad taste in the organization’s collective memory that they’ll be hard to reuse effectively?

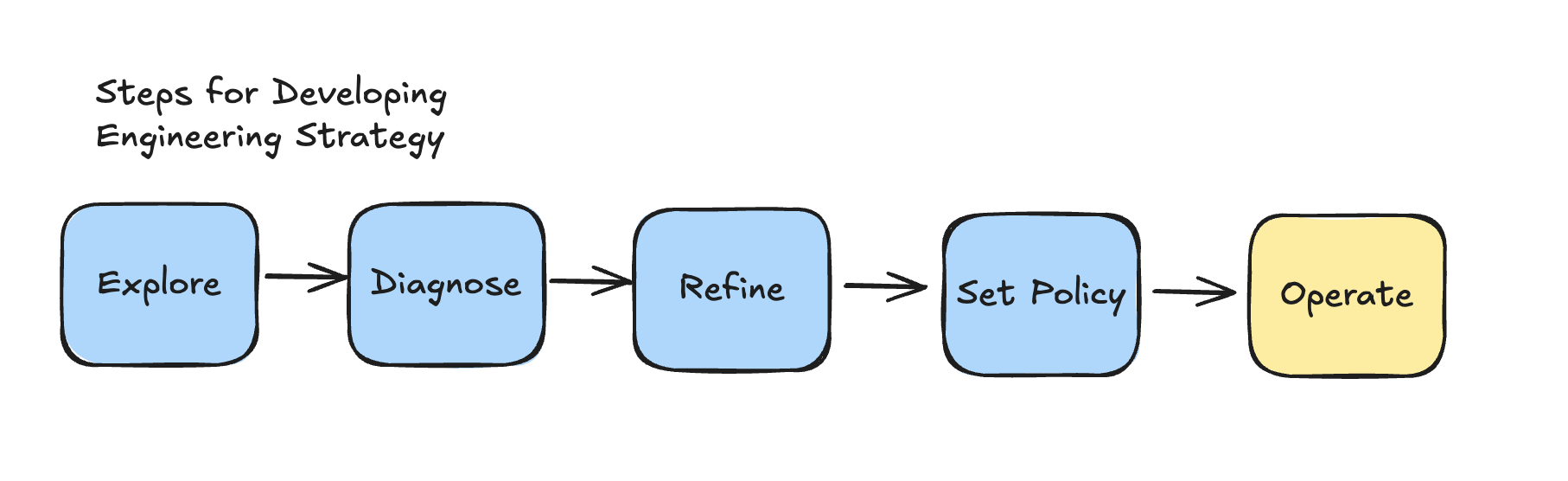

Which new mechanisms showed up in your exploration? In your exploration phase, you’ll frequently encounter mechanisms that your organization hasn’t previously tried. If any of them seem particularly well-suited to the policies you’re considering, and none of your organization’s frequently used mechanisms are good fits, then consider testing a new one.

Evaluate mechanisms against the evaluation rubric. For each of the mechanisms you’re considering using, apply the rubric from the above How to evaluate mechanisms to validate they’re good fits.

Consolidate into an operational plan. Now that you’ve determined the mechanisms you want to consider, work on fitting the full set of mechanisms into one coherent plan. Be particularly mindful of the ease, or burden, the integrated plan creates for both your users and platform providers.

Validate plan with users and providers. Many plans make sense from afar, but fail due to imposing an unreasonable burden. Or the burden might be acceptable, but the actual workflow simply won’t work at all.

Consider validating via strategy testing. If you run the above process, and can’t come to an agreement with stakeholders on your proposed plan, then simply commit to running a strategy testing process including the plan. This will create space for everyone to build confidence in the approach before they feel forced to make a commitment to following it long-term.

Even if you don’t use strategy testing for your plan, at least commit to scheduling a review in three months reflecting on how things have worked out.

Your operational plan is the vehicle that delivers your policies to your organization. It’s extremely tempting to skip refining the details here, but it’s a relatively quick step and will completely change your strategy’s outcomes.

Common mechanisms

Most companies have a handful of frequently used operational mechanisms. Some of those mechanisms are company specific, such as Amazon’s weekly business review, and others repeat across companies like requiring executive approval. Across the many mechanisms you’ll encounter, you can generally cluster them into recurring categories. This section covers the mechanisms I’ve found consistently effective.

Approval and advice forums

At a high level, new policies are obvious, simple and apply cleanly to the problem they are intended to solve. However, when you apply those policies to detailed, complex circumstances, it’s often ambiguous how to stay loyal to a policy’s intentions. Approval and advice forums are a common solution to that problem.

Calm’s product engineering strategy shows what the simplest, and most common, approval forum looks like in practice:

Exceptions are granted by the CTO, and must be in writing. The above policies are deliberately restrictive. Sometimes they may be wrong, and we will make exceptions to them. However, each exception should be deliberate and grounded in concrete problems we are aligned both on solving and how we solve them. If we all scatter towards our preferred solution, then we’ll create negative leverage for Calm rather than serving as the engine that advances our product.

All exceptions must be written. If they are not written, then you should operate as if it has not been granted. Our goal is to avoid ambiguity around whether an exception has, or has not, been approved. If there’s no written record that the CTO approved it, then it’s not approved.

This example also has several weaknesses that happen in many approval forums.

Most importantly, it doesn’t make it clear how to get approvals.

It would be stronger if it explicitly explained how to get an approval (perhaps go ask in #cto-approvals),

and where to find prior approvals to help someone considering requesting an exception to

calibrate their request.

Approvals don’t necessarily need to come from senior leadership. Instead, the senior leadership can loan their authority on a topic to another group. The LLM adoption strategy provides a good example of this:

Start with Anthropic. We use Anthropic models, which are available through our existing cloud provider via AWS Bedrock. To avoid maintaining multiple implementations, where we view the underlying foundational model quality to be somewhat undifferentiated, we are not looking to adopt a broad set of LLMs at this point. This is anchored in our Wardley map of the LLM ecosystem.

Exceptions will be reviewed by the Machine Learning Review in #ml-review

In a more community-minded organization, the approval forums might not require senior leadership involvement at all. Instead, the culture might create an environment where the forums’ feedback is taken seriously on its own merits.

Every company does approval forums a bit differently, ranging from our experiments at Carta with Navigators, granting executive authority for technical decisions to named engineers in each area, to Andrew Harmel-Law’s discussion of this topic in Facilitating Software Architecture. You can spend a lot of time arguing the details here, my experience is that having the right participants and a good executive sponsor matter a lot, and the other pieces matter a lot less.

Inspection

While even the best policies can fail, the more common scenario is that a policy will sort-of work, and need some modest adjustments to make it more successful. An inspect mechanism allows you to evaluate whether your policy is succeeding and if you need to make adjustments.

The user-data access strategy provides an example:

Measure progress on percentage of customer data access requests justified by a user-comprehensible, automated rationale. This will anchor our approach on simultaneously improving the security of user data and the usability of our colleagues’ internal tools. If we only expand requirements for accessing customer data, we won’t view this as progress because it’s not automated (and consequently is likely to encourage workarounds as teams try to solve problems quickly). Similarly, if we only improve usability, charts won’t represent this as progress, because we won’t have increased the number of supported requests.

As part of this effort, we will create a private channel where the security and compliance team has visibility into all manual rationales for user-data access, and will directly message the manager of any individual who relies on a manual justification for accessing user data.

This example is a good start, but fully realizing an inspection mechanism requires concretely specifying where and how the data will be tracked. A better version of this would include a link to the dashboard you’ll look at, and a commitment to reviewing the data on a certain frequency.

For a recent inspection mechanism, I created a recurring invite with a link to the relevant data dashboard, and a specific chat channel for discussion, and invited the working group who had agreed to review the data on that cadence. This wasn’t a synchronous meeting, but rather a commitment to independently review, and discuss anything that felt surprising.

Your particular mechanisms could be threshold-triggered alerts, something you fold into an existing metrics review meeting, a script you commit to running and reviewing periodically, or something else. The most important thing is that it cannot silently fail.

Nudges

While it’s common to hear complaints about how a team isn’t following a new policy, as if it were a deliberate choice they’d made, I find it more common that people want to do things the new way, but rarely take time to learn how to do it. Nudges are providing individuals with context to inform them about a better way they might do something, and they are an exceptionally effective mechanism.

Grounding this in an example, at Stripe we had a policy of allowing teams to self-authorize introducing new cloud hosting costs. This worked well almost all the time. However, sometimes teams would accidentally introduce large cost increases without realizing it, and teams that introduced those spikes almost never had any awareness that they had caused the problem. Even if we’d told them they must not introduce unapproved spending spikes, they simply didn’t perceive they’d done it.

We had the choice between preventing all teams from introducing new spend, or we could try using a nudge. The nudge we added informed teams when their cloud spend accelerated month over month, directed to charts that explained the acceleration, and told them where to go to ask questions. Nudges pair well with inspections, and there was also a monthly review by the Efficiency Engineering team to review any spikes and reach out where necessary.

Maybe we could have forced all teams to review new spend, but this nudge approach didn’t require an authoritative mandate to implement. It also meant we only spent time advising teams that actually spent too much, instead of having to discuss with every team that might spend too much.

As another example making that point, a working group at Carta added a nudge to inform managers of untested pull requests merged by their team. Some managers had previously said they simply didn’t know when and why their team had merged untested pull requests, and this nudge made it easy to detect. The nudge also respected their attention by not sending a notification at all if there wasn’t a new, untested pull request.

With poor ergonomics, nudges can be an overwhelming assault on your colleagues attention, but done well, I continue to believe they are the most effective operational mechanism.

Documentation

Policies can’t be enforced by people who don’t know they exist, or by people who don’t know how to follow those policies. In my experience, nudges are the most effective way of solving both of those problems, because nudges bring information to people at exactly the moment that information would be useful. At most companies, well-done nudges are relatively uncommon, and the far more common solution to lack of information is documentation and training.

There are so many approaches to both of these topics, and I’ve not found my own approaches here particularly effective. Consequently, I am hesitant to give much advice on what will work best for you. The best I can offer is that following standard practices for your company, even if the outcomes seem imperfect, is probably your best bet. Internal knowledge bases tend to rot quickly, and introducing yet another knowledge base is almost always the illusion of progress rather than real progress. Even when you really don’t like the current one.

Finally, remember that success for documentation and training is not necessarily that everyone in the company knows how a new policy works. Instead, as discussed in the chapter on whether strategy is useful, a more useful goal is informational herd immunity: as long as someone on each team understands your policy, the team will generally be capable of following it.

Automation

Relying on humans to respond is slow, and the quality of human response is highly varied. In many cases, automation provides the most effective and most scalable mechanism to support your policies’ rollout.

Automation was key in the Uber service migration strategy, moving us out of a manual, slow process that was taking up a great deal of user and provider time:

Move to structured requests, and out of tickets. Missing or incorrect information in provisioning requests create significant delays in provisioning. Further, collecting this information is the first step of moving to a self-service process. As such, we can get paid twice by reducing errors in manual provisioning while also creating the interface for self-service workflows.

In that case, better automation allowed us to eliminate a series of back-and-forth negotiations to collect data, and to instead get the necessary information in a single step. Occasionally we still ran into users who couldn’t fill in the form, but now we could focus on providing a good manual experience for those rare exceptions.

As you use automation as a core strategy mechanism, it’s important to recognize that designing an effective user experience is a prerequisite to automation having a positive impact. If you view the user experience of your automation as a secondary concern, then you are unlikely to make much impact with automation.

Deferment to future work

Sometimes there’s something you really want a policy to do, but you also know that you have no reasonable mechanism to do it. In that case, you may find explicitly deferring action on the topic useful.

The strategy for integration of the Index acquisition at Stripe uses this mechanism:

Defer making a decision regarding the introduction of Java to a later date: the introduction of Java is incompatible with our existing engineering strategy, but at this point we’ve also been unable to align stakeholders on how to address this decision. Further, we see attempting to address this issue as a distraction from our timely goal of launching a joint product within six months.

We will take up this discussion after launching the initial release.

As did the strategy for working with a private equity acquirer:

We believe there are significant opportunities to reduce R&D maintenance investments, but we don’t have conviction about which particular efforts we should prioritize. We will kickoff a working group to identify the features with the highest support load.

There’s no shame in deferral. As much as you want to make progress on a certain area, it’s better to explicitly acknowledge that you can’t make progress on it–and clarify when you will be able to–then to allow the organization to churn on an intractable problem.

Meetings

Meetings are the final mechanism, and you can fit any and all of the above mechanisms into a meeting. They are a universal mechanism, although frequently overused because they can do an adequate job of operating almost any policy.

The most common mechanism is a reporting meeting, such as reporting progress in the Executive Weekly Meeting as suggested in the LLM adoption strategy:

Develop an LLM-backed process for reactivating departed and suspended drivers in mature markets. Through modeling our driver lifecycle, we determined that improving onboarding time will have little impact on the total number of active drivers. Instead, we are focusing on mechanisms to reactivate departed and suspended drivers, which is the only opportunity to meaningfully impact active drivers.

Report on progress monthly in Exec Weekly Meeting, coordinated in #exec-weekly

The other common meeting archetype is the weekly working meeting introduced in the chapter on strategy testing. Meetings are almost always the most expensive mechanism you can find to solve a problem, but they are easy to suggest, run, and iterate on.

If you can’t find any other mechanism you believe in, then a meeting is a decent starting point. Just don’t get too fond of them, and try to iterate your way to canceling every meeting that you start.

Anti-patterns

In addition to the effective operational methods discussed above, there are a number of additional mechanisms that are frequently used, but which I consider anti-patterns. They can provide some value, but there’s almost always a better alternative.

Top-down pronouncements: Sometimes a policy will be operationalized by simply declaring it must be followed. It’s common to see a leader declare that a policy is now in effect, assuming that the announcement is a useful way to implement the new policy.

For example, some “return to office” policies dictate that the team must work from their office, but driving a real change requires motivating those individuals to actually return.

Education-as-announcements rollouts: The default way that many companies roll out policies is through one-time “education,” often as an all-company announcement for existing employees. They might follow up by updating training for onboarding new-hires. Education sounds great, but a couple of trainings will never change organizational behavior.

Changing behavior requires ongoing reminders, visible role models, inspection to understand why some teams are not adopting the behavior, and so on. Education can be a good component of operationalizing a policy, but it cannot stand on its own.

Mandatory recurring trainings: These are a staple of compliance driven policies, generally because of laws which require providing a certain number of hours of relevant training each year.

There are two deep challenges with mandatory trainings. First, because attendance is required, people tend to make little effort to make the content good. Second, many folks don’t pay attention because they expect the content to be low quality. It’s not uncommon to hear people say that they’ve never heard of a policy that they’ve performed annual training on for multiple years.

It’s possible to overcome these barriers, but in a situation where you’re accountable for changing outcomes, as opposed to shifting legal obligations away from the company, these tend to work poorly.

Just change the culture. Some leaders frame most problems as cultural problems, which is a reasonable frame: most things can be usefully viewed as a cultural problem. Unfortunately, it’s common for those who rely heavily on the cultural frame to also have a simplistic view about how culture is changed.

Changing an organization’s culture is tricky, and requires a combination of many techniques to create visible leaders role modeling the new behavior, and reinforcement mechanisms to ensure pockets of dissent are weeded out. Anyone who frames culture change as a simple or instant change is living in an imaginary world.

If you’re using one of these approaches, it isn’t necessarily a bad choice. Instead, you should just make sure you can explain why you’re using it, and then you need to also make sure you believe that explanation. If you don’t, look for a mechanism from the earlier

What if you’re not an executive?

It’s easy to get discouraged when you think about which operational mechanisms are available to you as a non-executive. So many of the frequently seen mechanisms like running mandatory recurring meetings, or a binding architecture review process are not accessible to you.

That is true: they’re not accessible to you. However, there’s always a related mechanism that can be implemented with less authority. The binding architecture process can be replaced with an architectural advice process. The mandatory review of pull requests can be replaced with a nudge.

Although it may be more common to see the authoritative mechanisms in the companies you work in, my experience working as an executive is that these authoritative mechanisms don’t work particularly well. They do a great job of technically shifting accountability to the wider organization, but they often don’t change behavior at all. So, instead of getting frustrated by what you can’t do, focus instead on the mechanisms that are available to you today. Add nudges, focus on the real dynamics of how colleagues do work in your organization, and build a real dataset.

It’s very hard to get an executive to support your initiative before the mechanisms and data exist to support it, and very easy to get their support once they do. Once you’ve done what you can without authority to build confidence, if you really do need more authority, then you’re in a good place to escalate to get an executive to support your policies.

Beware cargo-culting

The longer that I am in the industry, the more I am surprised by how few strategists seem to care if their approach actually works. Instead, they seem focused on doing something that might work, offloading accountability to either the organization or some team, and then moving off to the next problem.

Perhaps this is driven by an unfortunate reality that leaders are often evaluated by how they appear, rather than by what they accomplish. Whether or not that’s the underlying reason for why it happens, it does make it surprisingly difficult to know which patterns to borrow from strategy rollouts and implementations.

The best advice, unfortunately, is to remain skeptically optimistic. Collect ideas widely, but force the ideas to prove their merit.

Summary

Now that you’ve finished this chapter, you’re significantly more qualified to write a complete, useful strategy than I was a decade into my career. Often skipped, the operations behind your strategy are at least as essential as any other step, and any strategy without them will fade quietly into your organization’s history.

In addition to being able to rollout a strategy of your own, this chapter also provides a useful rescue toolkit you can use to put an existing, floundering strategy back on track. If you don’t see an opportunity to write new strategy within your organization, then there’s still probably room to flex your operational skill.