Inclusion in the first shift.

Several years and an employer ago, I was interviewing a candidate for an engineering management role and asked them how they built diverse teams. They mentioned the pipeline problem and, with a pained expression, self-administered a common benediction: it’s just really hard.

Most management loops ask a variant of this question today, but most candidates get visibly uncomfortable and few are proud of their answer. Me too. For the longest time, I felt a sense of dread even asking the question, marking down their answer against a rubric while tallying the low marks I’d assign my own.

As an infrastructure engineering leader, stability will always be the golden priority for me and my team. But at the start of 2017, I wanted to improve myself in an area that I’ve been intimidated by, and few topics made me more uncomfortable than nurturing an inclusive organization. I can’t speak from a place of wisdom, but hopefully I can speak from a place of learning, and I’ve written up some of the inclusion work we did over the past year.

Measurement

Drucker suggests, “If you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it”, and that’s where I started. Especially when you invest a bunch of your time and energy into something, it’s easy to index on your effort over your effect, so starting with success metrics was important to keep me grounded in real impact.

I started measuring the areas proposed by Lara Hogan in Inclusion math, and added a few more based on discussion with coworkers and friends:

- Retention: do underrepresented minorities (URMs) stay at your company as long as other folks?

- Time at level: do URMs experience comparable rates of career progression at your company?

- Level distribution: are URMs represented in all levels of seniority?

- Compensation: are URMs compensated equitably for their level?

- Usage rate: which individuals lead and participate in inclusion and culture efforts? Are senior managers and senior engineers involved? How broad is the pool of participants?

- Social recognition: do you talk about inclusion efforts in your forums of culture? Company meetings, offsites, and so on.

- Performance recognition: how are inclusion and culture efforts recognized in your performance and compensation process?

- Hiring: is your pipeline diverse, and are URMs in your pipeline getting and accepting offers at similar rates? (The pipeline still matters.)

Many of these metrics are easy to analyze in partnership with human resources. Much of what we did to impact those metrics is obvious (e.g. cold sourcing), and I don’t want to retread tired ground, but measuring and moving some of these metrics did require meaningful changes to how I work, and I think those are worth digging into a bit.

Selecting project leaders

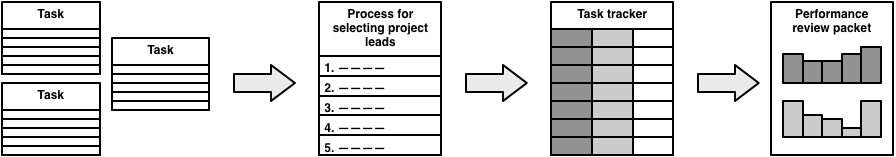

One place I had to entirely change my habits was around selecting folks to lead important projects. This emerged from my coworker Franklin pushing back with a seemingly simple question, “How did you select the person to lead that project?” The real answer–that they happened to be nearby–was too uncomfortable to acknowledge, so I hemmed and hawed for a bit. I realized this was an area of opportunity for the broader team, and we developed a structured process for selecting project leaders.

While we’re still iterating, our approach is roughly:

- Send a email to internal mailing list announcing the project. Outline the project, the expected time commitment, and skills that you anticipate being important. I try to make the price of applying as low as possible; in recent notes I’ve added “if you’re not sure if you’re well suited but are interested, apply anyway” to encourage folks who might be uncertain.

- Give folks at least three business days to privately volunteer by sending you an email. The combination of private application and extended application period is meant to reduce the performance art aspect of volunteering, and give folks time to discuss with their manager. Over time I’ve also found that it helps a great deal to privately encourage folks to volunteer.

- Select the best applicant based on the necessary skills. Balance between the company priorities of today–to deliver the project–and the company priorities of tomorrow: to build a large leadership bench.

- Reply to the initial thread letting folks know who was selected.

- Add a note in a spreadsheet somewhere of the folks who applied and who was selected to lead the project.

- Review the spreadsheet to understand if you’re relying too heavily on some folks for some kinds of projects.

This has been powerful in creating transparency around opportunities to lead important projects, and also in building a broader bench of leadership. We’re still early days, but we’ve seen more folks get involved, and see them involved in different areas of work they wouldn’t have previously thought to participate in. Interestingly, the actual process of picking someone to lead the project is not inherently any more fair in this approach–it’s still me picking the person I believe is best suited–but the transparency and documentation helps me learn from my decisions over time.

You don’t have to run this process for everything! It’s pretty slow for small stuff, but you can still add a row to your spreadsheet to track decisions when you do something more informal.

Recognition

Once you’ve structured selecting folks to lead projects, another important step is recognizing them! This is especially important for inclusion and maintenance projects, as well as projects run well enough to avoid heroics, which often receive limited recognition.

We made mostly informal efforts to socially recognizing inclusion and maintenance projects, and we were more structured in our approach to recognizing efforts in our performance reviews. Most importantly, Julia rewrote our engineering ladder, with a strong focus on citizenship, which helped ground the conversation.

Ending thoughts

Early in 2017, when I decided that inclusion was my second highest priority for the year, it was far from an obvious outcome. As an engineering leader I was a necessary ally, but not a likely one: I’ve always been uncomfortable with the discussion, and most often found focusing on my own challenges. It was only thanks to learning from many folks I work with, especially AnnE, Franklin and Julia, that I found my path off the sidelines.

Today, if someone asked me how to build an inclusive, diverse team, I’m still uncomfortable imagining what my answer. However, I’m no longer draped in the learned helplessness that made “It’s just very hard” my best answer. There is a long way to go, but reflecting on the progress over the past year, I can be authentically optimistic that anyone–even me!–can learn to nurture an inclusive, diverse organization that folks are proud to participate in.