Good hypergrowth/curator manager.

In 2016, I wrote Productivity in the age of hypergrowth to discuss the challenges of engineering management during periods of hypergrowth. Managers in such periods spend much of their time on hiring and onboarding, with the remainder devoted to organizational structure and high-level strategy. Their technical expertise is important, but it’s demonstrated indirectly in the quality of their strategy, structure, and hiring.

In 2023, our universe has shifted. There’s little hiring happening, and most companies are eliminating roles to meet investor and market pressure to operate in an environment where fundraising new cash is significantly more expensive. The role of engineering management has changed as well. Hiring and onboarding are now secondary components of our work, strategy and structure are elevated, and there’s a demand for us to employ our technical expertise more directly.

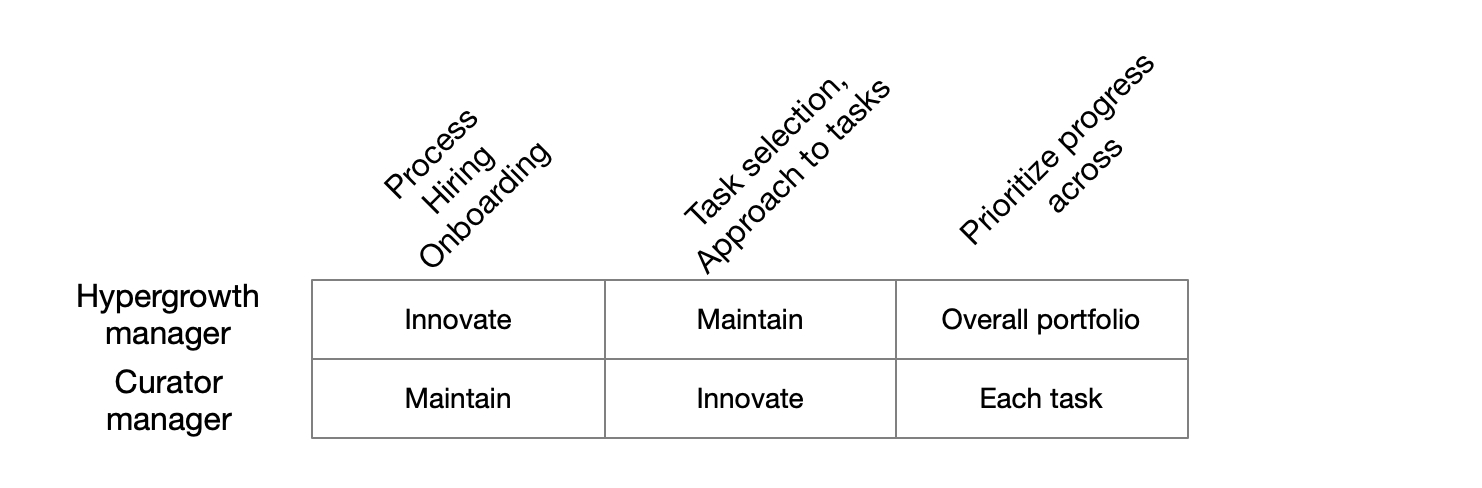

My experience is that this shift is real, has been relatively subtle, and hasn’t really been directly acknowledged in any discussion I’ve had over the past couple years. Consequently, I wanted to write up a short comparison between the “hypergrowth manager” and “curator manager” archetypes, in the spirit of Ben Horowitz’s Good Product Manager/Bad Product Manager. This list reads a bit skeptical of hypergrowth management, but that’s to better articulate the distinction: both are valid approaches to different situations.

Good curator/hypergrowth managers:

- Curators don’t spend time arguing internally for headcount, because they know the headcount ins’t coming; they create more impact by picking the right work and ensuring that work’s effective implementation. Hypergrowers know that headcount growth will solve most current problems in the long-run

- Curators view every project as essential, ensuring their team’s work is successful short-term, and that it ladders up into a larger strategy over time that accelerates the team’s impact. Hypergrowers have so many bets that they focus on a portfolio approach where only some, not all, bets need to gain traction

- Curators are in the data to align their team with the real opportunity, and are stubborn about starting work whose premise doesn’t connect with their understanding of the data. Hypergrowers know that the underlying shape of the data is changing rapidly and their mental model may easily be out of date since last month

- Curators treat hiring and onboarding as one-off projects, and know that the hire has to fit into their specific team. Hypergrowers treat hiring and onboarding as a program, and know that the memberships of each team will change significantly over the next year

- Curators lead teams of real, specific individuals, and work to find task-individual fit. Hypergrowers lead teams of rapidly shifting individuals where tasks and individuals shift too often to optimize task-individual fit

- Curators know that growth won’t fix their organizational missteps, and engage with issues directly (e.g. if a team is too small to handle an on-call rotation, they merge teams). Hypergrowers know that missteps will be solved indirectly by organizational growth without requiring direct resolution

- Curators know that team morale is a precious resource, and invest explicitly into maintaining morale. Hypergrowers know that the rapid expansion of the company’s valuation will paper over most morale issues

- Curators find ways to grow their career that avoid artificial competition with colleagues. Hypergrowers often make the mistake of viewing career growth through the size of their team

- Both know that poor quality and technical debt will slow forward progress, even though time is constrained for different reasons

- Both prefer properly sized teams of 6-8 engineers

Shifting elevation, a few thoughts about Directors and VPs operating in these modes, which I’ll lump together using the term “executives” for ease of use:

- Curator executives are judged by their execution against a rotating spotlight of emergencies. Hypergrowth executives are judged by the outcomes of their diversified portfolio of bets

- Curator executives know that their ultimate impact is derived from systemic changes to culture and durable investments, but that they’ll be judged almost entirely on managing emergencies: real success comes from successfully managing both dimensions. Hypergrowth executives know that there will be emergencies constantly, that they’ll burn out quickly if they personally address each one, and focus instead on managing their portfolio of bets: success comes from maintaining altitude as emergencies try to pull you in

- Curator executives work with their teams to fully resolve fires. Hypergrowth executives mitigate fires until they can be handed off to newly hired managers for resolution

- Curator executives generally solve problems directly. Hypergrowth executives generally work via programs. Both prefer to work the policy rather than solve via exceptions

- Curator executives anchor on reality as perceived by their engineers. Hypergrowth executives anchor on reality as perceived by their engineering managers

- Curator executives are deep in the margin profile and revenue plan. Hypergrowth executives maximize revenue growth without deteriorating margin much

- Curator executives design organizations that are steady-state durable. Hypergrowth executives design organizations that minimize the impact of frequent expansions

As an ending thought, if you have a suggestion for a better term than “curator”, let me know. The first term that came to mind for me was “steward manager” but there’s an implication of passiveness that misses the mark. Replacing “manager” with “leader” is unhelpful because it misses the reality that these folks are still managers and fundamentally doing management work.