"Good engineering management" is a fad

As I get older, I increasingly think about whether I’m spending my time the right way to advance my career and my life. This is also a question that your company asks about you every performance cycle: is this engineering manager spending their time effectively to advance the company or their organization?

Confusingly, in my experience, answering these nominally similar questions has surprisingly little in common. This piece spends some time exploring both questions in the particularly odd moment we live in today, where managers are being told they’ve spent the last decade doing the wrong things, and need to engage with a new model of engineering management in order to be valued by the latest iteration of the industry.

If you’d be more interested in a video version of this, here is the recording of a practice run I gave for a talk centered on these same ideas (slides from talk).

Good leadership is a fad

When I started my software career at Yahoo in the late 2000s, I had two 1:1s with my manager over the course of two years. The first one came a few months after I started, and he mostly asked me about a colleague’s work quality. The second came when I gave notice that I was leaving to join Digg. A modern evaluation of this manager would be scathing, but his management style closely resembled that of the team leader in The Soul of A New Machine: identifying an important opportunity for the team, and navigating the broader organization that might impede progress towards that goal. He was, in the context we were working in, an effective manager.

Compare that leadership style to the expectations of the 2010s, where attracting, retaining, and motivating engineers was emphasized as the most important leadership criteria in many organizations. This made sense in the era of hypergrowth, where budgets were uncapped and many companies viewed hiring strong engineers as their constraint on growth. This was an era where managers were explicitly told to stop writing software as the first step of their transition into management, and it was good advice! Looking back we can argue it was bad guidance by today’s standards, but it aligned the managers with the leadership expectations of the moment.

Then think about our current era, that started in late 2022, where higher interest rates killed zero-interest-rate-policy (ZIRP) and productized large language models are positioned as killing deep Engineering organizations. We’ve flattened Engineering organizations where many roles that previously focused on coordination are now expected to be hands-on keyboard, working deep in the details. Once again, the best managers of the prior era–who did exactly what the industry asked them to do–are now reframed as bureaucrats rather than integral leaders.

In each of these transitions, the business environment shifted, leading to a new formulation of ideal leadership. That makes a lot of sense: of course we want leaders to fit the necessary patterns of today. Where things get weird is that in each case a morality tale was subsequently superimposed on top of the transition:

- In the 2010s, the morality tale was that it was all about empowering engineers as a fundamental good. Sure, I can get excited for that, but I don’t really believe that narrative: it happened because hiring was competitive.

- In the 2020s, the morality tale is that bureaucratic middle management have made organizations stale and inefficient. The lack of experts has crippled organizational efficiency. Once again, I can get behind that–there’s truth here–but the much larger drivers aren’t about morality, it’s about ZIRP-ending and optimism about productivity gains from AI tooling.

The conclusion here is clear: the industry will want different things from you as it evolves, and it will tell you that each of those shifts is because of some complex moral change, but it’s pretty much always about business realities changing. If you take any current morality tale as true, then you’re setting yourself up to be severely out of position when the industry shifts again in a few years, because “good leadership” is just a fad.

Earlier this summer, I also gave a presentation at the YCombinator CTO summit on this specific topic of the evolution of engineering management. You can watch a recorded practice run of that talk on YouTube as well, and see the slides.

Self-development across leadership fads

If you accept the argument that the specifically desired leadership skills of today are the result of fads that frequently shift, then it leads to an important followup question: what are the right skills to develop in to be effective today and to be impactful across fads?

Having been and worked with engineering managers for some time, I think there are eight foundational engineering management skills, which I want to personally group into two clusters: core skills that are essential to operate in all roles (including entry-level management roles), and growth skills whose presence–or absence–determines how far you can go in your career.

The core skills are:

Execution: lead team to deliver expected tangible and intangible work. Fundamentally, management is about getting things done, and you’ll neither get an opportunity to begin managing, nor stay long as a manager, if your teams don’t execute.

Examples: ship projects, manage on-call rotation, sprint planning, manage incidents

Team: shape the team and the environment such that they succeed. This is not working for the team, nor is it working for your leadership, it is finding the balance between the two that works for both.

Examples: hiring, coaching, performance management, advocate with your management

Ownership: navigate reality to make consistent progress, even when reality is difficult Finding a way to get things done, rather than finding a way that it not getting done is someone else’s fault.

Examples: doing hard things, showing up when it’s uncomfortable, being accountable despite systemic issues

Alignment: build shared understanding across leadership, stakeholders, your team, and the problem space. Finding a realistic plan that meets the moment, without surprising or being surprised by those around you.

Examples: document and share top problems, and updates during crises

The growth skills are:

Taste: exercise discerning judgment about what “good” looks like—technically, in business terms, and in process/strategy. Taste is a broadchurch, and my experience is that broad taste is an somewhat universal criteria for truly senior roles. In some ways, taste is a prerequisite to Amazon’s Are Right, A Lot.

Examples: refine proposed product concept, avoid high-risk rewrite, find usability issues in team’s work

Clarity: your team, stakeholders, and leadership know what you’re doing and why, and agree that it makes sense. In particular, they understand how you are overcoming your biggest problems. So clarity is not, “Struggling with scalability issues” but instead “Sharding the user logins database in a new cluster to reduce load.”

Examples: identify levers to progress, create plan to exit a crisis, show progress on implementing that plan

Navigating ambiguity: work from complex problem to opinionated, viable approach. If you’re given an extremely messy, open-ended problem, can you still find a way to make progress? (I’ve written previously about this topic.)

Examples: launching a new business line, improving developer experience, going from 1 to N cloud regions

Working across timescales: ensure your areas of responsibility make progress across both the short and long term. There are many ways to appear successful by cutting corners today, that end in disaster tomorrow. Success requires understanding, and being accountable for, how different timescales interact.

Examples: have an explicit destination, ensure short-term work steers towards it, be long-term rigid and short-term flexible

Having spent a fair amount of time pressure testing these, I’m pretty sure most effective managers, and manager archetypes, can be fit into these boxes.

Self-assessing on these skills

There’s no perfect way to measure anything complex, but here are some thinking questions for you to spend time with as you assess where you stand on each of these skills:

- Execution

- When did your team last have friction delivering work? Is that a recurring issue?

- What’s something hard you shipped that went really, really well?

- When were you last pulled onto solving a time-sensitive, executive-visible project?

- Team

- Who was the last strong performer you hired?

- Have you retained your strongest performers?

- What strong performers want to join your team?

- Which peers consider your team highly effective?

- When did an executive describe your team as exceptional?

- Ownership

- When did you or your team overcome the odds to deliver something important? (Would your stakeholders agree?)

- What’s the last difficult problem you solved that stayed solved (rather than reoccurring)?

- When did you last solve the problem first before addressing cross-team gaps?

- Alignment

- When was the last time you were surprised by a stakeholder? What could you do to prevent that reoccuring?

- How does a new stakeholder understand your prioritization tradeoffs (incl rationale)?

- When did you last disappoint a stakeholder without damaging your relationship?

- What stakeholders would join your company because they trust you?

- Taste

- What’s a recent decision that is meaningfully better because you were present?

- If your product counterpart left, what decisions would you struggle to make?

- Where’s a subtle clarification that significantly changed a design or launch?

- How have you inflected team’s outcomes by seeing around corners?

- Clarity

- What’s a difficult trade-off you recently helped your team make?

- How could you enable them to make that same trade-off without your direct participation?

- What’s a recent decision you made that was undone? How?

- Navigating ambiguity

- What problem have you worked on that was stuck before assisted, and unstuck afterwards?

- How did you unstick it?

- Do senior leaders bring ambiguous problems to you? Why?

- Working across timescales

- What’s a recent trade off you made between short and long-term priorities?

- How do you inform these tradeoffs across timescales?

- What long-term goals are you protecting at significant short-term cost?

Most of these questions stand on their own, but it’s worth briefly explaining the “Have you ever been pulled into a SpecificSortOfProject by an executive?” questions. My experience is that in most companies, executives will try to poach you onto their most important problems that correspond to your strengths. So if they’re never attempting to pull you in then either you’re not considered as particularly strong on that dimensions, or you’re already very saturated with other work such that it doesn’t seem possible to pull you in.

Are “core skills” the same over time?

While those groupings of “core” and “growth” skills are obvious groupings to me, what I came to appreciate while writing this is that some skills swap between core to growth as the fads evolve. Where execution is a foundational skill today, it was less of a core skill in the hypergrowth era, and even less in the investor era.

This is the fundamentally tricky part of succeeding as an engineering manager across fads: you need a sufficiently broad base across each of these skills to be successful, otherwise you’re very likely to be viewed as a weak manager when the eras unpredictably end.

Stay energized to stay engaged

The “Manage your priorities and energy” chapter in The Engineering Executive’s Primer captures an important reality that took me too long to understand: the perfect allocation of work is not the mathematically ideal allocation that maximizes impact. Instead, it’s the balance between that mathematical ideal and doing things that energize you enough to stay motivated over the long haul. If you’re someone who loves writing software, that might involve writing a bit more than helpful to your team. If you’re someone who loves streamlining an organization, it might be improving a friction-filled process that is a personal affront, even if it’s not causing that much overall inefficiency.

Forty-year career

Similarly to the question of prioritizing activities to stay energized, there’s also understanding where you are in your career, an idea I explored in A forty-year career.

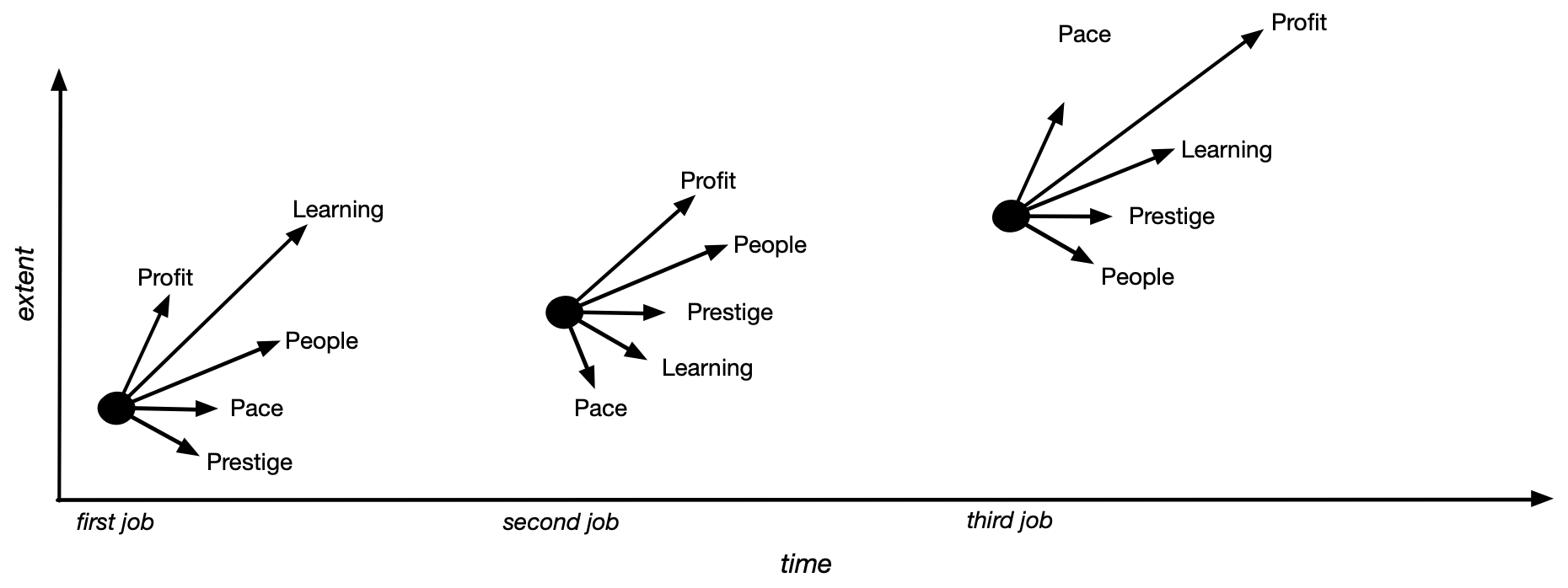

For each role, you have the chance to prioritize across different dimensions like pace, people, prestige, profit, or learning. There’s no “right decision,” and there are always tradeoffs. The decisions you make early in your career will compound over the following forty years. You also have to operate within the constraints of your life today and your possible lives tomorrow. Early in my career, I had few responsibilities to others, and had the opportunity to work extremely hard at places like Uber. Today, with more family responsibilities, I am unwilling to make the tradeoffs to consistently work that way, which has real implications on how I think about which roles to prioritize over time.

Recognizing these tradeoffs, and making them deliberately, is one of the highest value things you can do to shape your career. Most importantly, it’s extremely hard to have a career at all if you don’t think about these dimensions and have a healthy amount of self-awareness to understand the tradeoffs that will allow you to stay engaged over half a lifetime.