Make your peers your first team.

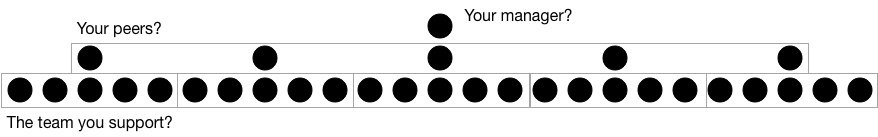

While companies are literally composed of teams, I’ve found it surprisingly common to find folks who feel like they are not a member of any team. Managers working directly with engineers tend to feel some membership in that team, but even the rarest occasions of authority create a certain distance. Managing managers lets you pierce the veil a bit more, but the curtain falls when it comes to performance management or assigning resources.

Looking towards your peers can be uncomfortable in a different way. As your span of responsibility grows, you may not know much of your peers’ work, or you may find yourself frequently contesting with them for constrained resources. Even when surrounded by in the fastest of growth, you may be awkwardly aware that you’re aspiring to move into the same, rare, roles.

These dynamics can lead to teams whose camaraderie is at best a qualified non-aggression pact, and collaboration is infrequent. It’s a strange tragedy that we hold ourselves accountable for building healthy, functional teams, and are so rarely on them ourselves.

But it can be better. It’s ok to expect more.

I’ve worked on a few teams where folks consistently looked out for each other, and believed they’d all come out better together. These were teams where folks were willing to disappoint the folks they managed in order to help their peers succeed. Not callously disappointing folks, but rather balancing outcomes from a broad perspective that included their peers.

The members of such a team have shifted their first team from the folks they support to their peers. While these teams are rare, I’ve come to believe that supporting their creation is simple–albeit hard–work, and when the conditions are fostered they lead to an exceptionally rewarding work environment.

The ingredients necessary for such a team are:

- Awareness of each other’s work. Even with the best intentions, a member cannot optimize for their team if they’re not familiar with each other’s work. The first step to moving someone’s identity to their peers is to ensure they know about their peers’ work. This will require a significant investment of time, likely in the form of sharing weekly progress, and the occasional opportunity for folks to dive deep into each other’s work.

- From character to person. When we don’t know someone well, we tend to project intentions onto them, casting them as a character in a play they themselves are unaware exists. It’s quite challenging to optimize on behalf of characters in your mental play, but it’s much easier to be understanding of folks you know personally. Spending time together learning about each other, often at a team offsite, will slowly transform folks into people.

- Refereeing defection. In game theory there is an interesting concept of a dominant strategy. A dominant strategy is one that is expected to return the maximum value regardless of the actions of other players. Team collaboration is not a dominant strategy. Rather, it depends on everyone participating together in good faith. If you see someone acting against the interests of the team, you, too, will likely defect to pursue your own self-interest. Some teams are tight knit enough that no one ever attempt defection, but most teams experience frequent changes in membership and external conditions. On such teams, I believe coordination is only possible when the manager or a highly respected member operates as a referee, holding folks accountable for good behavior.

- Avoiding zero-sum culture. Some companies foster zero-sum cultures, where perceived success depends on capturing scarce, metered resources like headcount. It’s hard to convince folks to coordinate under such conditions. Positive cultures center on recognizing impact, support and development, which are all avenues that support widespread success.

- Make it explicit. If you have the first four ingredients, I’ve found that you still have to explicitly discuss the idea of shifting folks’ identifies away from the team they support and toward the team of their peers. It’s hard to move membership from the team you spend the most time with, and I haven’t seen it happen organically.

Given how much energy it takes to shift a team of managers’ identities away from the folks they support and towards their peers, I think it’s quite reasonable to question whether it’s genuinely worth doing it. You’ll be unsurprised to know that I think it is.

As you move into larger roles, you’ll need to start considering challenges from the perspectives of more teams and people. In this sense, treating your peers as your first team allows you to begin practicing your manager’s job, without having to get promoted into the role first. The more fully you embrace optimizing for your collective peers, the closer your priorities will mirror your manager’s. Beyond practicing working from this broader lense, it will also position you for particularly useful feedback from your manager, as you’ll both be considering similar problems with shared goals.

The best learning doesn’t always come directly from your manager, and one of the most important things a first team does is provide a community of learning. Your peers can only provide excellent feedback if they’re aware of your work and are thinking about your work similarly to how you do. Likewise, as you’re thinking about your peers’ work, you’ll be able to learn from how they approach it differently than you anticipate. Soon, your team’s rate of learning will be the sum of each other’s challenges, not longer restricted to your own.

Long term, I believe that your career will be largely defined by getting lucky and the rate at which you learn. I have no advice about luck, but to speed up learning I have two suggestions: rapidly expanding company, and make your peers your first team.

Jason Wong’s Building a First Team Mindset is an excellent read on this theme if you’re looking for more!