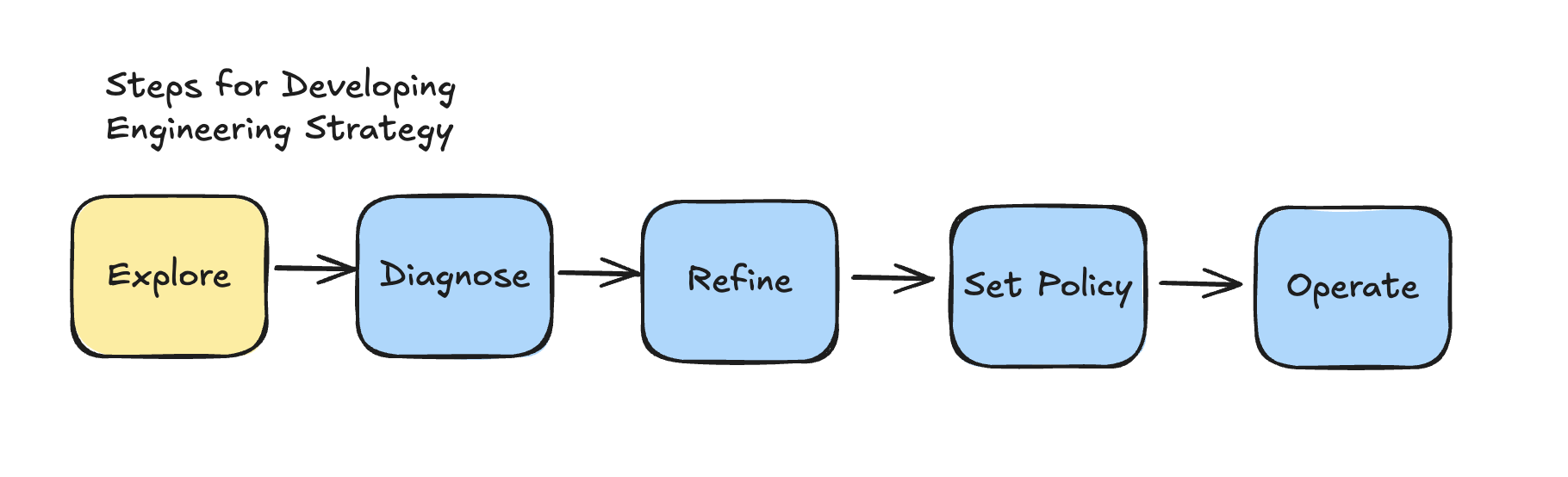

Exploring for strategy.

A surprising number of strategies are doomed from inception because their authors get attached to one particular approach without considering alternatives that would work better for their current circumstances. This happens when engineers want to pick tools solely because they are trending, and when executives insist on adopting the tech stack from their prior organization where they felt comfortable.

Exploration is the antidote to early anchoring, forcing you to consider the problem widely before evaluating any of the paths forward. Exploration is about updating your priors before assuming the industry hasn’t evolved since you last worked on a given problem. Exploration is continuing to believe that things can get better when you’re not watching.

This chapter covers:

- The goals of the exploration phase of strategy creation

- When to explore (always first!) and when it makes sense to stop exploring

- How to explore a topic, including discussion of the most common mechanisms: mining for internal precedent, reading industry papers and books, and leveraging your external network

- Why avoiding judgment is an essential part of exploration

By the end of this chapter, you’ll be able to conduct an exploration for the current or next strategy that you work on.

This is a chapter from Crafting Engineering Strategy.

What is exploration?

One of the frequent senior leadership anti-patterns I’ve encountered in my career is The Grand Migration, where a new leader declares that a massive migration to a new technology stack–typically the stack used by their former employer–will solve every pressing problem. What’s distinguishing about the Grand Migration is not the initially bad selection, but the single-minded ferocity with which the senior leader pushes for their approach, even when it becomes abundantly clear to others that it doesn’t solve the problem at hand.

These senior leaders are very intelligent, but have allowed themselves to be trapped by their initial thinking from prior experiences. Accepting those early thoughts as the foundation of their strategy, they build the entire strategy on top of those ideas, and eventually there is so much weight standing on those early assumptions that it becomes impossible to acknowledge the errors.

Exploration is the deliberate practice of searching through a strategy’s problem and solution spaces before allowing yourself to commit to a given approach. It’s understanding how others have approached the same problem recently and in the past. It’s doing this both in trendy companies you admire, and in practical companies that actually resemble yours.

Most exploration will be external to your team, but depending on your company, much of your exploration might be internal to the company. If you’re in a massive engineering organization of 100,000, there are likely existing internal solutions to your problem that you’ve never heard of. Conversely, if you’re in an organization of 50 engineers, it’s likely that much of your exploration will be external.

When to explore

Exploration is the first step of good strategy work. Even when you want to skip it, you will always regret skipping it, because you’ll inadvertently frame yourself into whatever approach you focus on first. Especially when it comes to problems that you’ve solved previously, exploration is the only thing preventing you from over-indexing on your prior experiences.

Try to continue exploration until you know how three similar teams within your company and three similar companies have recently solved the same problem. Further, make sure you are able to explain the thinking behind those decisions. At that point, you should be ready to stop exploring and move on to the diagnosis step of strategy creation.

Exploration should always come with a minimum and maximum timeframe: less than a few hours is very suspicious, and more than a week is questionable as well.

How to explore

While the details of each exploration will differ a bit, the overarching approach tends to be pretty similar across strategies. After I open up the draft strategy document I’m working on, my general approach to exploration is:

Start throwing in every resource I can think of related to that problem.

For example, in the Uber service migration strategy, I started by collecting recent papers on Mesos, Kubernetes, and Aurora to understand the state of the industry on orchestration.

Do some web searching, foundational model prompting, and checking with a few current and prior colleagues about what topics and resources I might be missing.

For example, for the Calm engineering strategy, I focused on talking with industry peers on tools they’d used to focus a team with diffuse goals.

Summarize the list of resources I’ve gathered, organizing them by which I want to explore, and which I won’t spend time on but are worth mentioning.

For example, the Large Language Model adoption strategy’s exploration section documents the variety of resources the team explored before completing it.

Work through the list one by one, continuing to collect notes in the strategy document. When you’re done, synthesize those into a concise, readable summary of what you’ve learned.

For example, the monolith decomposition strategy synthesizes the exploration of a broad topic into four paragraphs, with links out to references.

Stop once I generally understand how a handful of similar internal and external teams have recently approached this problem.

Of all the steps in strategy creation, exploration is inherently open-ended, and you may find a different approach works better for you. If you’re not sure what to do, try following the above steps closely. If you have a different approach that you’re confident in–as long as it’s not skipping exploration!–then go ahead and try that instead.

While not discussed in this chapter, you can also use some techniques like Wardley mapping, covered in the Refinement chapter, to support your exploration phase. Wardley mapping is a strategy tool designed within a different strategy tradition, and consequently categorizing it as either solely an exploration tool or a refinement tool ignores some of its potential uses.

There’s no perfect way to do strategy: take what works for you and use it.

Mine internal precedent

One of the most powerful forms of strategy is simply documenting how similar decisions have been made internally: often this is enough to steer how similar future decisions are made within your organization. This approach, documented in Staff Engineer’s Write five, then synthesize, is also the most valuable step of exploration for those working in established companies.

If you are a tenured engineer within your organization, then it’s somewhat safe to assume that you are aware of the typical internal approaches. Even then, it’s worth poking around to see if there are any related skunkworks projects happening internally. This is doubly true if you’ve joined the organization recently, or are distant from the codebase itself. In that case, it’s almost always worth poking around to see what already exists.

Sometimes the internal approach isn’t ideal, but it’s still superior because it’s already been implemented and there’s someone else maintaining it. In the long-run, your strategy can ride along as someone else addresses the issues that aren’t a perfect fit.

Using your network

How should we control access to user data’s exploration section begins with:

Our experience is that best practices around managing internal access to user data are widely available through our networks, and otherwise hard to find. The exact rationale for this is hard to determine,

While there are many topics with significant public writing out there, my experience is that there are many topics where there’s very little you can learn without talking directly to practitioners. This is especially true for security, compliance, operating at truly large scale, and competitive processes like optimizing advertising spend.

Further, it’s surprisingly common to find that how people publicly describe solving a problem and how they actually approach the problem are largely divorced.

This is why having a broad personal network is exceptionally powerful, and makes it possible to quickly understand the breadth of possible solutions. It also provides access to the practical downsides to various approaches, which are often omitted when talking to public proponents.

In a recent strategy session, a proposal came up that seemed off to me, and I was able to text–and get answers to those texts–industry peers before the meeting ended, which invalidated the room’s assumptions about what was and was not possible. A disagreement that might have taken weeks to resolve was instead resolved in a few minutes, and we were able to figure out next steps in that meeting rather than waiting a week for the next meeting when we’d realized our mistake.

Of course, it’s also important to hold information from your network with skepticism. I’ve certainly had my network be wrong, and your network never knows how your current circumstances differ from theirs, so blindly accepting guidance from your network is never the right decision either.

If you’re looking for a more detailed coverage on building your network, this topic has also come up in Staff Engineer’s chapter on Build a network of peers, and The Engineering Executive’s Primer’s chapter on Building your executive network. It feels silly to cover the same topic a third time, but it’s a foundational technique for effective decision making.

Read widely; read narrowly

Reading has always been an important part of my strategy work. There are two distinct motions to this approach: read widely on an ongoing basis to broaden your thinking, and read narrowly on the specific topic you’re working on.

Starting with reading widely, I make an effort each year to read ten to twenty industry-relevant works. These are not necessarily new releases, but are new releases for me. Importantly, I try to read things that I don’t know much about or that I initially disagree with. Some of my recent reads were Chip War, Building Green Software, Tidy First?, and How Big Things Get Done. From each of these books, I learned something, and over time they’ve built a series of bookmarks in my head about ideas that might apply to new problems.

On the other end of things is reading narrowly. When I recently started working on an AI agents strategy, the first thing I did was read through Chip Huyen’s AI Engineering, which was an exceptionally helpful survey. Similarly, when we started thinking about Uber’s service migration, we read a number of industry papers, including Large-scale cluster management at Google with Borg and Mesos: A Platform for Fine-Grained Resource Sharing in the Data Center.

None of these readings had all the answers to the problems I was working on, but they did an excellent job at helping me understand the range of options, as well as identifying other references to consult in my exploration.

I’ll mention two nuances that will help a lot here. First, I highly encourage getting comfortable with skimming books. Even tightly edited books will have a lot of content that isn’t particularly relevant to your current goals, and you should skip that content liberally. Second, what you read doesn’t have to be books. It can be blog posts, essays, interview transcripts, or certainly it can be books.

In this context, “reading” doesn’t even have to actually be reading. There are conference talks that contain just as much as a blog post, and conferences that cover as much breadth as a book. There are also conference talks without a written equivalent, such as Dan Na’s excellent Pushing Through Friction.

Each job is an education

Experience is frequently disregarded in the technology industry, and there are ways to misuse experience by copying too liberally the solutions that worked in different circumstances, but the most effective, and the slowest, mechanism for exploring is continuing to work in the details of meaningful problems.

You probably won’t choose every job to optimize for learning, but it allows you to explore more complex problems over time–recognizing that some of your prior knowledge will have gone stale along the way–which is uniquely valuable.

Save judgment for later

As I’ve mentioned several times, the point of exploration is to go broad with the goal of understanding approaches you might not have considered, and invalidating things you initially think are true. Both of those things are only possible if you save judgment for later: if you’re passing judgment about whether approaches are “good” or “bad”, then your exploration is probably going astray.

As a soft rule, I’d argue that if no one involved in a strategy has changed their mind about something they believed when you started the exploration step, then you’re not done exploring. This is especially true when it comes to strategy work by senior leaders. Their beliefs are often well-justified by years of experience, but it’s unclear which parts of their experience have become stale over time.

Summary

At this point, I hope you feel comfortable exploring as the first step of your strategy work, and understand the likely consequences of skipping this step. It’s not an overstatement to say that every one of the worst strategic failures I’ve encountered would have been prevented by its primary author taking a few days to explore the space before anchoring on a particular approach.

A few days of feeling slow are always worth avoiding years of misguided efforts.