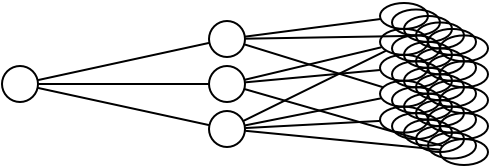

Cold sourcing: hire someone you don't know.

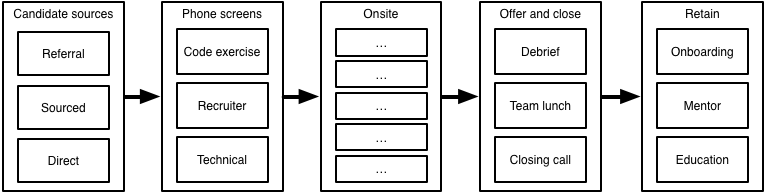

The three biggest sources of candidates are referrals from your existing team, inbound applicants who apply on your jobs page, and sourced candidates that you proactively bring into your funnel.

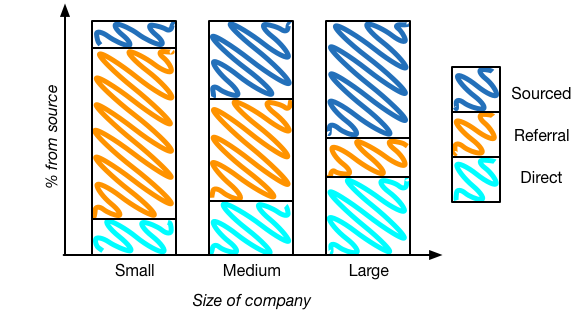

Small companies tend to rely on referrals, and large companies tend to rely on sourcing candidates, using dedicated recruiting sourcers for whom this is their full time job (often the first rung on a recruiter career ladder), and medium sized companies are somewhere on the continuum between those extremes. (Slack in particular has done some interesting work to encourage inbound applicants, and while they’re now getting to the size where most companies depend more heavily on sourced and direct applicants, I suspect inbound applicants are not their largest source of candidates.)

Hiring and recruiting teams tend to prefer referrals because they often have higher pass and accept rates, and most early stage companies, especially those without dedicated recruiting functions end up being primarily composed of referrals. (An interesting caveat: lately I’m seeing more of a second category of referral candidate, who are running their own extremely systematic interviewing process, with the aim of getting offers from three or more companies, and consequently tend to have much lower acceptance rates.)

Referrals come with two major drawbacks.

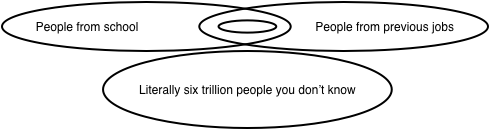

The first is that your personal network will always be quite small, especially when you consider the total candidate pool. This is especially true early in your career, but it’s easy to work for a long time without building out a large personal network if you work in a smaller market or at a series of small companies (one of the side benefits of working at a large company early in your career, beyond name recognition, is kickstarting your personal network).

The other issue is that folks tend to have relatively uniform networks composed of the folks they went to school with or worked with. By hiring within those circles, it’s easy to end up with a company that thinks, believes and sometimes even looks similarly.

Moving beyond your personal networks

Many hiring managers freeze up when their referral network starts to dry up or as they look to bring a wider set of backgrounds onto their teams, but the good news is that there is a simple answer: cold sourcing. Cold sourcing, a technique that’s also common in some kinds of sales, is reaching out directly to folks you don’t know.

If you’re introverted, this will probably be an extremely unsettling experience at first, with questions like “What if they’re annoyed by my email? What if I’m wasting their time?” ringing in your head. These are important questions, and we have an obligation to be thoughtful about how we inject ourselves into others’ lives. I was personally paralyzed by this concern initially, but ultimately I think it was unfounded: a concise, thoughtful invitation to discuss a job opportunity is an opportunity, not an infringement, especially for folks who are on career networking sites like LinkedIn. Most folks will ignore you (which is great), others will politely demur (also great), a few will actually respond (even greater), and a surprisingly amount will ignore you for six months and then pop up mentioning that they’re starting a new job search: I’ve never had someone respond unkindly.

The other great thing about cold sourcing is that it’s pretty straightforward, and I’ll share the approach I’ve used, with the caveat that I believe there are a tremendous number of different approaches that are probably more effective. Take this as a good starting point, track your results, and then experiment!

Your first cold sourcing recipe

My standard approach to cold sourcing is:

Join LinkedIn. I suspect variations of this technique would work on other networks (e.g. Github), but the challenge is that folks on other networks are generally not looking to engage about employment opportunities, and intent increases response rate significantly! (A good parallel here is search versus display advertising, where search advertising has an order of magnitude higher click-through rates as folks are actually searching for what they’re being advertised.)

Build out your network by following folks you actually do know. Add everyone that you went to school with, have worked with, have interacted with on Twitter, etc. It’s important to seed your network with some people you know because it’ll increase the reach of your second degree network, and it’ll also reduce the rate at which folks mark you as someone they don’t know (which is an input to being penalized as a spammer).

Be patient. If your initial network is small, it’s very likely that you’ll get throttled pretty frequently. Once you’re throttled (you’ll get a message along the lines of “you’ve exceeded your search capacity for this month”), you’ll have to wait for a few days, potentially until the next month, to unthrottle. (Alternatively, you could sign up for their premium products, which would accelerate this quite a bit.) It may take weeks or months of occasional effort (schedule an hour each week) to get your network large enough that you’re able to perform more than a few searches without ratelimiting. Anecdotally, the number of connections where things seem to get easier is around six hundred or so.

Use the search function to identify second degree connections to connect to with. Start out by searching in your 2nd degree network by job title,

software engineerorengineering manager, and as your network expands consider switching from title to company. (Consider the various lists of great companies to find companies to search by.) Build a broadchurch of connections! Even folks whom you end up not reaching out to now are folks who might reach out to you later, or that you might reach out to in a few months as your hiring priorities change. If you’re not sure, just go ahead and do it.When someone accepts your connection request, grab their email address from their profile and send them a short, polite note inviting them to coffee or a phone call, and sharing with them a link to your job description. Experiment with varying degrees of customization. (If you’re having trouble finding their email, make sure you click “Show more” in their “Contact and Personal Info” section, and that they’re a first degree connection. A few folks don’t share their email at all, and I’d recommend moving on, alternatively you could send them a LinkedIn message directly.) I’ve personally found that customization matters less than I assumed, because folks mostly choose to respond based on their circumstances, not the quality of your note. (As a caveat, it’s possible to write bad notes that discourage folks from responding. Iterating on your reach out notes and getting a few other folks with different perspectives to review your note is a quick and high leverage thing to do.)

Your reachout notes can be very straightforward:

Hi $THEIR_NAME, I'm an engineering manager at $COMPANY, and think you would be a great fit for $ROLE (link to your job description). Would you be willing to grab a coffee or do a phone call to discuss sometime in the next week? Best, $YOUR_NAMEReally, I think it can be that simple! If that seems too simple, then run an A/B test with something more personalized or sophisticated.

It’s worth noting that you will end up connecting with some folks who you simply don’t have a great fit for right now. That’s ok. I recommend reviewing their profile pretty rigorously after they accept your connection, and making an honest assessment on fit. If you don’t have something, that’s ok, and it’s a better use of the candidate’s time to not reach out to them. (However, I also think we tend to over filter on qualities that don’t matter too much! Being respectful of the candidate’s time is, in my opinion, the most important to optimize for.)

Schedule and enjoy your coffees and chats, and remember that even folks you aren’t able to work with now are still folks you’re likely to work with next year or next job. Especially in Silicon Valley, it’s a very small network, and interact with each person like they’ll be providing feedback on whether or not to hire you at your next job (they very well might!). You have two goals for each of these calls or coffees: figure out if there is good mutual fit between the candidate and the role, and there is a good fit, then try to get them to move forward with your process. The three things I find most useful to folks deciding to move forward with our process are explaining why I personally am excited about the company and role we’re discussing, explain how our process works from our current chat to them receiving an offer, and leaving ample time to ask questions.

Keep spending an hour each week adding more connections and following up with folks who have connected. It’s a bit of a grind at times, but it’s definitely a practice that rewards consistency. I’ve found that this is a good activity to do together! Have a weekly meeting of folks who come together and source, chatting about how you’re evolving your search, and also to keep folks overcome their initial discomfort with cold reachouts. (It’s worth pointing out that this is much easier to with an applicant tracking system like Lever or Greenhouse, which allows you to have a single place to track if a candidate has already been contacted by someone else at your company. Having a bunch of folks from the same company reach out around the same time can paint a picture of chaos.)

If you’ve read through this, and are quite confident that this approach won’t work, I’m with you: before I tried it, I was similarly certain it wouldn’t work for me, and that it was just a big waste of time, but I’ve slowly been converted. It’s also important to recognize that very likely this exact approach won’t perform well over time: try something simple, push through your concerns that block you from starting, and then experiment with different approaches.

Is this high-leverage work?

Similarly, a frequent followup question is whether sourcing is a high leverage task for engineering managers. I think it is: folks are more excited to chat with someone who’d be managing them then they are to chat with a recruiter who they’ll mostly work with during the interview process, likewise, I think it’s a valuable signal showing that managers care about hiring enough to invest their personal energy and attention into it.

That said, I would be cautiously concerned if an engineering manager was spending more than an hour a week on sourcing (not including follow up chats, those will take up a bunch more time), there is a lot of important work to be done closing and evaluating candidates as well, in addition to the numerous non-hiring related opportunities to be helpful.

As a closing thought, the single clearest indicator of strong recruiting organizations is a close, respectful partnership between the recruiting and engineering functions. Spending some time cold sourcing is a great way to build empathy for the challenges that face recruiters on a daily basis, and it’s also an awesome opportunity to learn from the recruiters you partner with! We’ve been doing weekly cold sourcing meetings as a partnership between our engineering managers and engineering recruiters, and it’s been a great forum for learning, empathy building and, of course, hiring.

Thanks to Steve, TR and Malthe for reviewing versions of this post.