Career levels, designation momentum, etc.

I discussed the foundation of performance management systems in Designations, levels and calibrations, but the fundamentals can be a bit bland! What’s really interesting are the rough edges and unexpected emergent behaviors that come into play when you start to design and run these performance systems with lots of real people involved. These topics are particularly interesting to me because they are entirely unplanned but crop up consistently at pretty much every company as they scale.

Because they show up consistently, it’s possible to be prepared for them, rather than being caught by surprise. Since surprise is the cardinal sin of performance management, they often create a bunch of trouble for managers earlier in their career, and hopefully these notes will help you navigate these confusing waters!

Designation momentum. The natural tendency for a performance process to consistently produce the same evaluations for the same people despite changes in performance. If you are receiving good designations, this is an exciting phenomenon, because it means you are likely to continue receiving them. But I find it’s unexpectedly somewhat demotivating for high performers, who want consistent, direct feedback on their work so they can keep improving. Folks receiving poor designations, unsurprisingly, find this phenomenon quite frustrating, in particular because it makes it challenging for them to determine if its a lagging indicator of a previous issue or if they’re continuing to do poorly.

Many folks rely entirely on their manager to come up with a step-by-step path to high performance. That only works when designation momentum is taking you in a direct you’re happy with. If it’s not, you need to be the active participant in your success.

Propose a set of clear goals to your manager, and iterate together towards an explicit agreement on the expectations to hit the designation you’re aiming for. The goals need to be ambitious enough that your manager can successfully pitch the difficulty to their peers during calibration. If your manager is pushing back on your goals’ ambition, that is probably their way of saying they think their peers will challenge their difficulty. That doesn’t mean your plan isn’t difficult enough–it may well be very appropriate–but it does mean you’ll have to work to help them be able to explain why the goals are appropriate.

Designation momentum occurs for individuals, but it also happens for teams and organizations. For teams in this position, setting clear goals is a good start, but it’s also necessary to align with your peers and leadership about why your work is important. It’s your work as a leader to explain why your work is important in terms that the organization understands and appreciates, and this is a good example of where the failure to do so will have long-running costs.

Tit for tat. Calibrations systems without strong process and fair referees can degrade into tit-for-tat favor trading. It’s exceedingly rare to see active collusion during calibration, rather the most common case occurs when folks are silent instead of raising concerns. This silence may seem benign, but it isn’t: it pushes all responsibility for consistent outcomes onto individuals refereeing the calibration process.

Encouraging engagement requires the calibration referee to model the behavior, but more importantly depends on building psychological safety and trust across the folks who are calibrating together.Level expansion. As a company ages, it will inevitable add levels to support career progression. This happens even if a company remains the same size, and is primarily driven by company age, not size. This is frequently driven by a small cohort of the highest level folks.

If a company is experiencing particularly frequent level expansion, it is usually a sign that progression, compensation or recognition has been overly-tied to your level system, and you should identify mechanisms to reduce pressure on leveling. Training and education are useful here, as is getting more structured in assigning important projects.The other scenario that typically leads to level expansion is hiring of very senior folks from other, typically older, companies. These folks have benefited from level expansion at that company aged, and it’s hard for them to walk away from that heady cocktail of status, compensation and recognition.

Level drift. Because level expansion is typically driven more by the need for career progression than by the introduction of objectively distinct accomplishment, levels added at the top create downward pressure on existing levels. Expectations at a given level decrease over time.

This inflation feels uncomfortable because we often rely on scarcity to determine value, but it’s very uncommon for folks to adjust compensation in response to level drift, so in practice it is a rising tide that raises all boats. From a company perspective, it’s important to manage level drift explicitly, which makes it possible to apply the shifts consistently.

Opening of the gates. The combination of level expansion and level drift leads to periodic bursts where a cohort of folks cross level boundaries together. This happens most frequently at the highest-minus-one level, one or two cycles after a level expansion.

As a manager, it’s critical to coordinate with your peers to ensure that you are opening the gate together in a consistent fashion. It’s easy to miss these moments, which can inadvertently eject individuals from their natural cohort of peers. You can usually fix this in a subsequent cycle, but you’ll have missed out on momentum. After each cycle, take an hour and try to guess where the gates might open next, and talk with your peers about it.

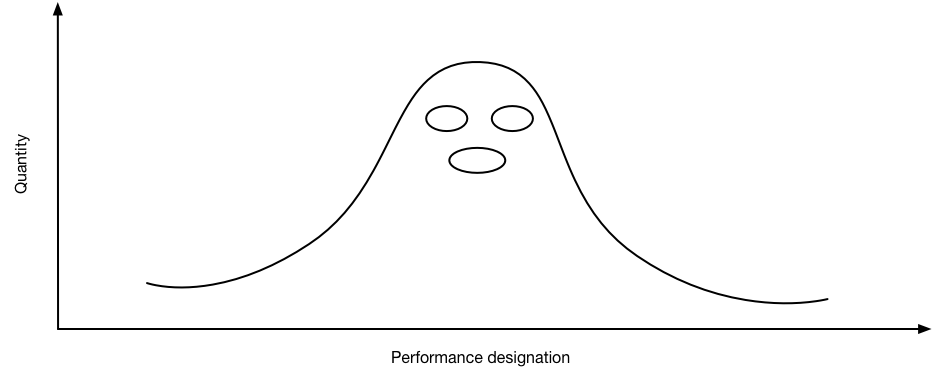

Career level. For every role, a given level will be established as the career level, and most folks are not expected to progress beyond that level. Over time, this often leads to career level clustering, with the normal distribution centered on the career level, as opposed to the typical goal of the distribution centering at mid-level.

Time at level limits. Folks who haven’t yet reached career level are expected to progress towards the career level at a consistent pace. Typically used as a backstop for situations where performance management seems appropriate but is not occuring. My experience is that most companies have time-at-level limits, but that there are many other ways to accomplish the same goals: useful as part of an overall system, but not necessary in many configurations. The only bit I’ve found predictably important here is being consistent in how they are applied.

Level split. Over time, it is common for the career level to experience level drift, leading to increasingly distinct clusters of folks who reached career level at its highest expectations and folks who have reached it recently. Given the greatly elevated expectations beyond the career level, upward mobility remains evasive. Many companies decide to perform a level split: separating the career level into two halves.

This allows the distinct cohorts to inhabit distinct levels, and extends the runway of career progression for most employees. Less obviously, the split tends to solidify the moat guarding access to post-career levels. The extended moat doesn’t catch the folks right on the border, it’s easy to handle them properly, but it absolutely does slow the progression for the cohort who were about a year away from changing levels.

Crisis designations. Alternatively, retention-driven designations. Sometimes companies find themselves in a difficult situation, where they have key individuals or even key teams that they consider to be at risk, and one of the tools for addressing the situation is to recognize their importance through elevated performance designations. This are intended as temporary, but tend to reset expectations permanently in ways that sacrifice long-term usefulness of the performance system to manage through short-term difficulty. Sometimes stuff gets real hard, and if that’s the case, then use the tools at your disposal, but generally try to avoid doing this if possible.

There are, surely, hundreds more interesting topics when it comes to how performance systems work in practice as opposed to in design. Although they seem quite simple, I keep learning something new each time I go through a performance cycle, and I suspect that is a widely shared experience.