Black Lives Matter.

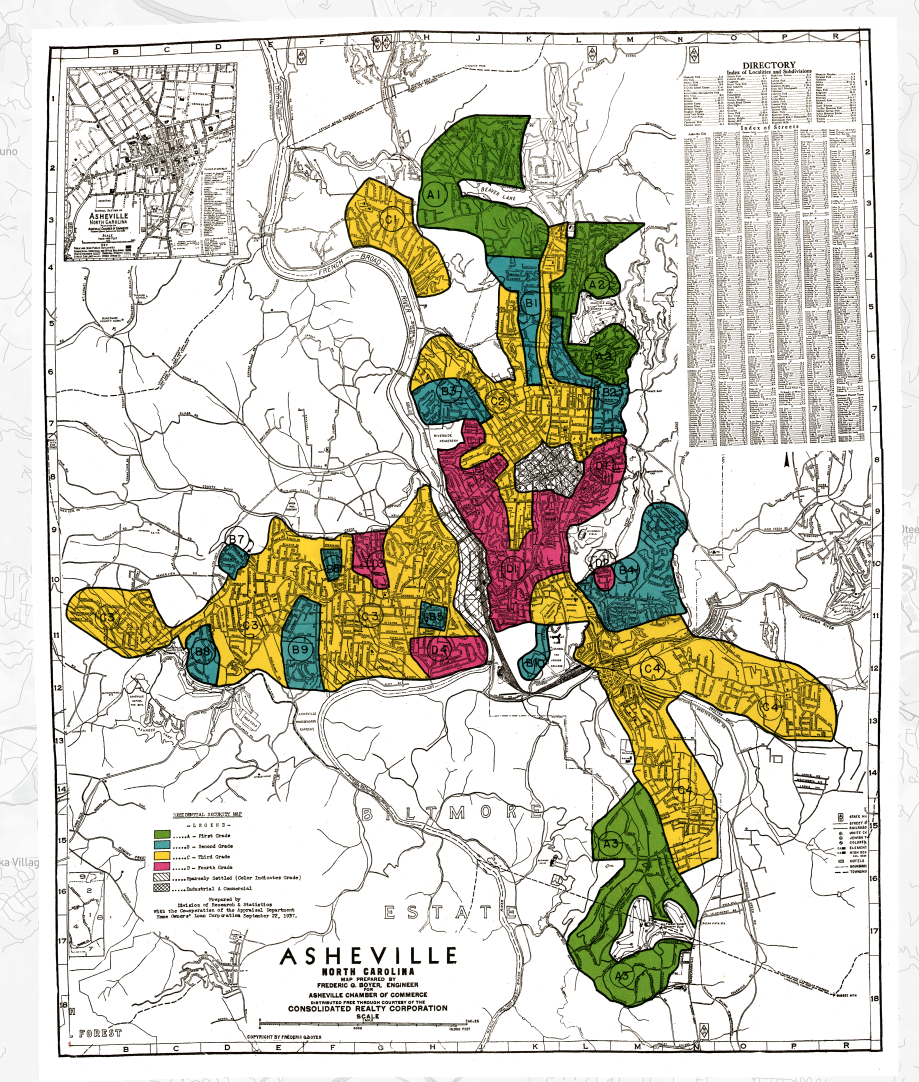

Redlining map of Asheville from Mapping Inequality.

Last Wednesday evening I was (virtually) at an event that started with a silent moment in the memory of George Floyd. I wasn’t expecting it but appreciated the moment before it moved on to other topics. That silent moment came back to me the next morning, and threw into sharp contrast the extent that George Floyd’s death simply didn’t exist within the communities where I spend the majority of my time.

His death didn’t exist in my spaces in the same way that Ahmaud Arbery’s death didn’t exist in my spaces, nor did Breonna Taylor’s among the uncountable others. Like most people, I go to sleep at night thinking of myself as a principled person with strong moral convictions, but in this moment a veil dropped and I suddenly saw how acutely absent I’d been in acknowledging George Floyd’s senseless death and those before it.

In that moment, for the first time in my life I was finally able to reach beyond viewing the killing of a Black man as a tragic injustice and to encounter an urgent and unexpected grief. I’ve previously believed that experiencing this grief was in essence a theft of others’ grief, but this ̉week I understood that not only is the well of grief infinite, but as a white American this grief is not someone else’s but indeed this grief is mine.

Growing up in Asheville, North Carolina, I remember taking a field trip in middle school to “The Block”, taught to us as an area so dangerous even police were scared to respond to calls. We read newspaper articles where we learned the neighborhood was only recently improving thanks to city investment.

Visiting my parents two decades later, we walked the Hood Tour with DeWayne Barton. I learned that “The Block” had been a flourishing area of Black homes and entrepreneurship that was systematically disassembled by the same city that would later take credit for restoring it. The same city whose tourists flock downtown to enjoy the Vance Monument, built to honor a slave-owning segregationist, and the same city whose prominent streets–Patton, Merrimon, McDowell–are named after prominent slave-owning families.

In learning this historical context, I was also forced to recognize how many of my own, nominally logical, beliefs were engines that perpetuated these injustices. In a discussion of redirecting Charlotte Street, it was obvious to me that you ought to demolish the lower value homes, not understanding why those homes had lower values or how it was the latest in a cycle of similarly calculated destruction. Charlotte Street, too, is named after an Asheville slaveholding family, this time Charlotte Patton, and certainly not Queen Charlotte as I’d idly assumed living a block away.

Growing up in the fine American tradition of celebrating the historic progress made by the Civil Rights movement, I never understood A Raisin in the Sun’s existential worry that history might loop rather than progress. Progress was too obvious to dispute. Studying Malcolm X’s The Ballot or the Bullet as a historical work, I imagined what it might have felt like to live in that moment.

Rereading his words yesterday, another veil dropped, and this time his words didn’t feel like history. They felt a lot more like now.